Good evening, Flight Simmers and History Buffs! Today we’re returning to Cuba in the historic Autumn of 1962 and touring sites related to the Cuban Missile Crisis. Get comfortable because this tour is another long one, traversing just over 600 nautical miles from San Julian to Guantanamo Bay, and requiring one fuel stop and two “tactical bladder breaks.”

Pee-Wee says: This tour blossomed after I found Nag’s copy of Robert Kennedy’s book “13 Days” on the shelf and gave it a quick read. That lead me to ask “where were the missile sites located?” That lead to the Internet, and declassified CIA files, and Google Earth, and more reading, and digging through hundreds of photos, and latitudes and longitudes, and Nag telling me to come to bed, and me losing complete track of time, and…well, here we are! ![]()

We jumped into the MonsterNX Cub again, although we didn’t anticipate any off-field landings. That autopilot sure is helpful!

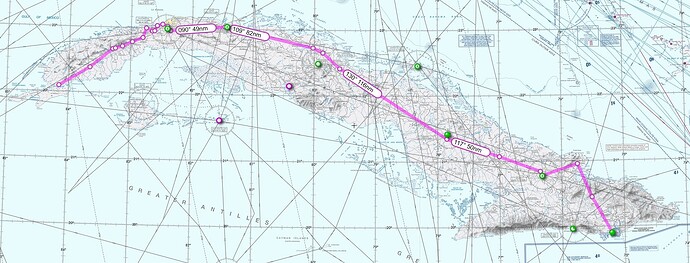

Here’s our planned route. We started at San Julián Air Base (MUSJ) in the province of Pinar del Río near the western tip of Cuba, some 130 nautical miles southwest of Havana, and headed generally east toward Guantanamo Bay. Along the way we spotted current and former air bases, surface-to-air missile (SAM) sites, abandoned military posts, and of course, the abandoned medium and intermediate-range ballistic missile (MRBM and IRBM) sites that triggered the Crisis.

Let’s review the basics of the Cuban Missile Crisis (the Caribbean Crisis in Russia or the October Crisis in Cuba). By 1962 the World was fully engulfed in a Cold War characterized by continuous research, development, and deployment of ever more powerful nuclear weapons by the United States (US) and Soviet Union (USSR). The US was undeniably leading with approximately 1,600 strategic bombers and 200 intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) versus the Soviet Union’s paltry 160 bombers and 38 ICBMs. Both sides fielded MRBMs, IRBMs, and submarine launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs), with numerical and technical superiority again going to the Americans. Were it not for its nearly 2:1 advantage in conventional forces in Europe, the Soviet Union would have been completely outclassed.

Pee-Wee says: In 1962 the Soviets decided to level the field by placing MRBMs and IRBMs in Cuba, where they could threaten targets throughout the entire United States. The operation–codenamed Anadyr–relied on total secrecy: it was deemed essential to only reveal the missiles’ presence after they were operational to prevent early intervention by the United States. It almost worked, but the Amercans’ more advanced strategic and tactical reconnaisance capabilities revealed the subterfuge in October 1962.

The United States responded by “quarantining” Cuba from international sea traffic, and the standoff began.

Pee-Wee says: An actual blockade would have been considered an act of war, and a potentially fatal escalation for both sides.

Only through the diplomatic efforts of President Kennedy and Premier Kruschev–and a healthy dose of luck–did the world avoid an atomic cataclysm. Barely two weeks after the Crisis erupted, the two sides struck a deal that removed the Soviets’ missiles from Cuba and the Americans’ similar missiles from Turkey.

Pee-Wee says: The Cuban Missile Crisis confirmed the importance of manned strategic and tactical reconnaissance aircraft. For months before the Crisis erupted, the CIA had photographed the whole of Cuba using U-2s. When the SAM threat appeared, the mission was handed to the Strategic Air Command’s 4080th Strategic Wing and the men of the 4028th Strategic Reconnaissance Squadron at Laughlin AFB in Texas. Low altitude photography was tasked to the US Navy’s VFP-62 and Marine Corps’ VMCJ-2 (Vought RF-8A Crusader) and the Air Force’s 363th Tactical Reconnaissance Wing (McDonnell RF-101C Voodoo). Navy P-2 Neptunes and new P-3A Orions monitored Russian shipping, and ERB-47s Stratojets of the 55th Strategic Reconnaissance Wing provided ELINT and SIGINT from offshore. (Note: the Crusader’s Wikipedia page references VFP-63 also serving over Cuba, but I’ve found no other source to confirm that squadron’s involvement.)

Well, that’s the basics out of the way, so let’s jump into the Monster and get going. We selected a solid gray version registered N343XX in homage to the recon crews flying over Cuba.

Pee-Wee says: The significance of the registration will become clear later. ![]()

![]() Let Slip the Dogs of War: San Julián Air Base

Let Slip the Dogs of War: San Julián Air Base

MSFS: 22.098 -84.156

Skyvector: 220553N0840922W

San Julián was established during World War 2 as a maritime patrol base for US blimps (Pee-Wee: Yay! ![]() ) and anti-submarine aircraft. During the Missile Crisis, the Soviet Union deployed Ilyushin Il-28 (NATO: “Beagle”) of the 759th Mine and Torpedo Aviation Regiment here. The first of thirty-three aircraft arrived in crates from Bahia Honda on Cuba’s north coast around October 14th. Assembly of the jet-powered medium bombers began immediately and the first aircraft, an Il-28U (NATO: “Mascot”) trainer, flew on October 30th.

) and anti-submarine aircraft. During the Missile Crisis, the Soviet Union deployed Ilyushin Il-28 (NATO: “Beagle”) of the 759th Mine and Torpedo Aviation Regiment here. The first of thirty-three aircraft arrived in crates from Bahia Honda on Cuba’s north coast around October 14th. Assembly of the jet-powered medium bombers began immediately and the first aircraft, an Il-28U (NATO: “Mascot”) trainer, flew on October 30th.

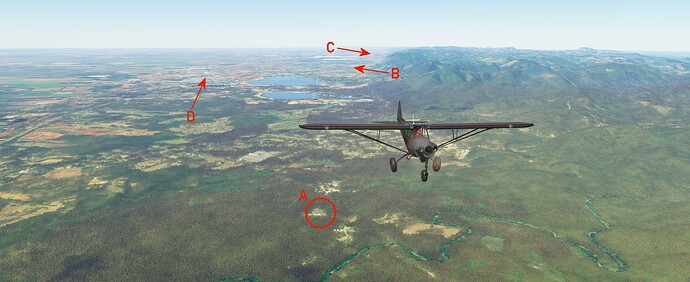

Here we are circling south of San Julián just after takeoff. In this screenshot you can see: (A) the main ramp area where Il-28s were reassembled and prepared for flight, (B) the expanded support area where maintenance and flight crews were housed, and (C) a single S-75 Dvina (NATO: SA-2 “Guideline”) SAM site. The airbase is open in MSFS, although current satellite photos indicate that the field is abandoned.

Cuba is a land of geological extremes, with broad plains pierced by rugged mountains in the island’s northwest, central, and southeast. In the distance you can see the Guaniguanico Mountain Range, and in the distant right near the edge of this photo is the city of Pinar Del Río.

Pee-Wee and I didn’t realize that the Il-28s arrived so late to the party. The 759th MTAR’s Beagles were trucked to San Julián on 14 October 1962, the same day the US first photographed MRBMs at San Cristobal Site #2 near Los Palacios, and the first aircraft didn’t fly until three days after Kennedy and Kruschev reached their historic agreement that essentially ended the Crisis.

A disagreement over the Il-28s soon developed between the Americans and Soviets. The Americans believed that the Beagles constituted “offensive weapons” and were subject to the Kennedy-Kruschev agreement. The Russians disagreed, saying the bombers were not only defensive but antiquated and posed no threat to the United States. A settlement was finally reached, and the 759th MATR packed up their toys and went home, arriving back in the Soviet Union on 30 December 1962. No aircraft or crews were lost during the deployment. A fascinating account by one of the squadron’s maintainers can be read here.

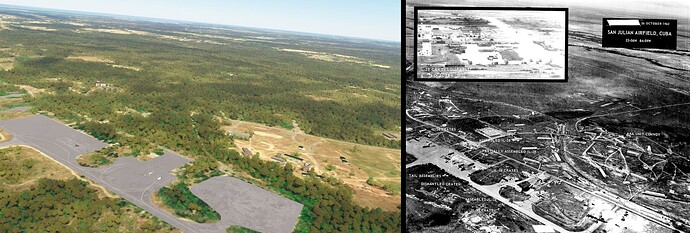

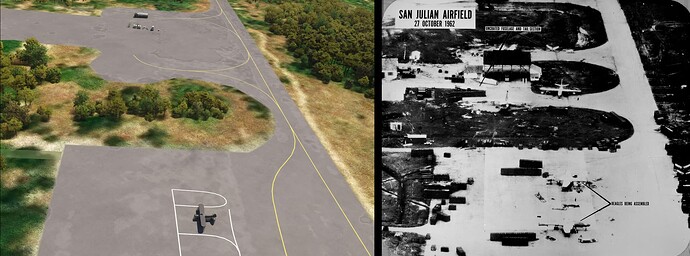

Pee-Wee says: After our flight, I went back and took these screenshots based on actual photos snapped by Navy Crusaders on 26 and 27 October 1962. They’re not perfect but show just how little the air base has changed in sixty-two years.

![]() The Rising Tide: La Coloma Air Base and S-75 Site

The Rising Tide: La Coloma Air Base and S-75 Site

La Coloma Air Base

MSFS: 22.337 -83.642

Skyvector: 222013N0833831W

La Coloma S-75 Site

MSFS: 22.325833 -83.581667

Skyvector: 221933N0833454W

Here we are flying northeastward at 3,500 feet in the vicinity of Pinar Del Río, looking south. There are two locations of interest here: (A) a former S-75 SAM site and (B) the La Coloma Air Base. We weren’t able to discover what activity occurred here during the crisis, or if any Cuban or Soviet combat units were stationed here. The fact that a SAM site was placed in such close proximity leads us to believe that something important was here. La Coloma later served as a training field with L-39 Albatross jets.

This real photo of the La Coloma SAM site is famous for being captured on color film. The National Photographic Interpretation Center built a scale model of this site for the Cuban Missile Crisis exhibit at the CIA’s headquarters in 1965. The Agency donated the model to the Smithsonian when the exhibit was closed in the 1970s.

Pee-Wee says: This one gave us some trouble! We knew where the La Coloma SAM site was supposed to be, but the latitude and longitude placed it in the middle of the Embalse El Punto, a reservoir south of Pinar Del Río. Without further information and having only extremely limited satellite imagery, we concluded that the reservoir was constructed between 1962 and 1985, and that the former SAM site now lies underwater.

![]() The Tip of the Spear: The San Cristobal MRBM Sites

The Tip of the Spear: The San Cristobal MRBM Sites

Site #1 “San Diego de Los Banos”

MSFS: 22.668 -83.298

Skyvector: 224005N0831753W

Site #2 “Los Palacios”

MSFS: 22.679 -83.254

Skyvector: 224044N0831514W

Site #3 “San Cristobal”

MSFS: 22.713 -83.138

Skyvector: 224247N0830817W

Site #4 “Candelaria”

MSFS: 22.782 -82.979

Skyvector: 224655N0825844W

Starting approximately 70 nautical miles northeast of San Julián Airbase, we found the first of four MRBM sites located along the southern fringe of the Sierra del Rosario (“Rosario Mountains”), part of the Guaniguanico Range. These sites hosted the 51st Missile Division’s 539th and 546th Missile Regiments, each with four launch pads for R-12 Dvina (NATO: SS-4 “Sandal”) MRBMs. From here, the Soviets could attack targets in the United States as distant as Denver, Minneapolis, and Bangor, and other places such as Mexico City, Bogota, Quito, and the Panama Canal. Most worrisome, the Atlas and Titan missile fields and a large number of strategic bombers and their refueling tankers in the central US were within range of the Soviet’s missiles.

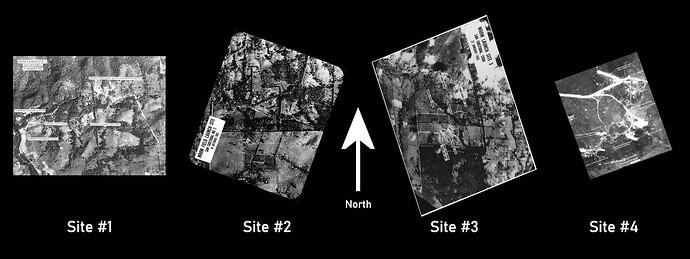

All the MRBM sites in Cuba were similar in design, and included up to four missile launch pads with erectors, control bunkers, large “ready tents” for maintaining and preparing up to twelve missiles, barracks and facilities for the missile crews, secure bunkers for storing nuclear warheads, and anti-aircraft artillery. When the Soviets removed the missiles, they all but erased evidence of their presence. Today, only a few fractured structures remain buried beneath overgrown forests.

Here we are flying northeast over Site #1 near San Diego de Los Banos, looking northwest. Visible in this screenshot are: (A) the nuclear warhead storage and preparation shed, which remains intact today, (B) the former tent camp where 539th Missile Regiment and construction crews barracked during construction, and the locations of the three completed launch pads (C, D, and E). This area was returned to local farmers after the Crisis abated, but taken over again by the Cuban military in 1965 as a training ground. The former warhead shed served briefly as a school house before supporting the training of Cuban troops destined for Angola in 1975.

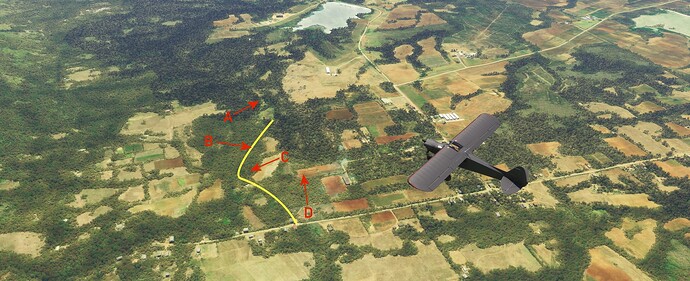

Pee-Wee says: In this screenshot we’re looking southeast. That’s Site #2 down there, a few miles north of Los Palacios. I’ve marked the following locations: (A) former missile ready tents, (B) the roadway on which a missile convoy was spotted on 14 October 1962, confirming the presence of MRBMs, (C) an open storage area, and (D) the former tent camp for 539th Missile Regiment crews. The yellow line marks the location of the former road that bisected the site, and which still exists up to (C).

Site #3 is more intact that the previous two. We’re looking roughly due east in this screenshot. The entry roads are still plainly visible running parallel in the center of this screenshot, the northern road underneath (H) and the southern road against the well-defined treeline across the field to the right. You can see the (A, B, C, and D) former launch pads, (E) former missile ready tents, (F) six-gun anti-aircraft artillery position, (G) the former support area where numerous permanent buildings were constructed, and (H) the nuclear warhead storage bunker. This site and #4 near Candelaria were operated by the 546th Missile Regiment.

Pee-Wee says: Site #4 was apparently never completed, so there wasn’t much to see. It’s visible at (A). Looking southwest, you can barely make out (B) Site #3 and (C) Sites #1 and #2. To the south is (D) San Cristobal. On the right, the Sierra Del Rosario rolls northward before dropping down to Cuba’s northern coast west of Mariel and Havana. Sites #1 and #4 are separated by approximately 22 nautical miles.

Pee-Wee says: Here’s a reference picture I put together to help you visualize these four sites. Each photograph is oriented with north “up.”

From here we continued northeastward toward Havana. Unfortunately, we’ve blown through our ten-photo limit, so we’ll continue the tour in Part 2.