Pee-Wee says: Before we start, I’m going to publicly thank a member of the FlightSim community. If you frequent flightsim.to, you know him as jamespejam. All of the aircraft skins he’s created for MSFS are digital masterpieces and marvelous to behold in their accuracy and execution.

Several weeks ago, I enlisted his talents to create a custom scheme to some very exacting specifications specifically for this Skytour, and he delivered in spades, massaging the tiniest details while I sat on the sideline and tossed rocks at him. The final result is…well, you’ll see for yourselves!

Thank you, T.O. Hopefully we’ll do your work justice today. ![]()

–V.F.

Welcome to a special Sky Tour, history buffs! Today we’re heading to the northwest coast of France and the Cherbourg Peninsula, an area occupied by the descendants of Viking invaders who lent their name to this region: Normandy.

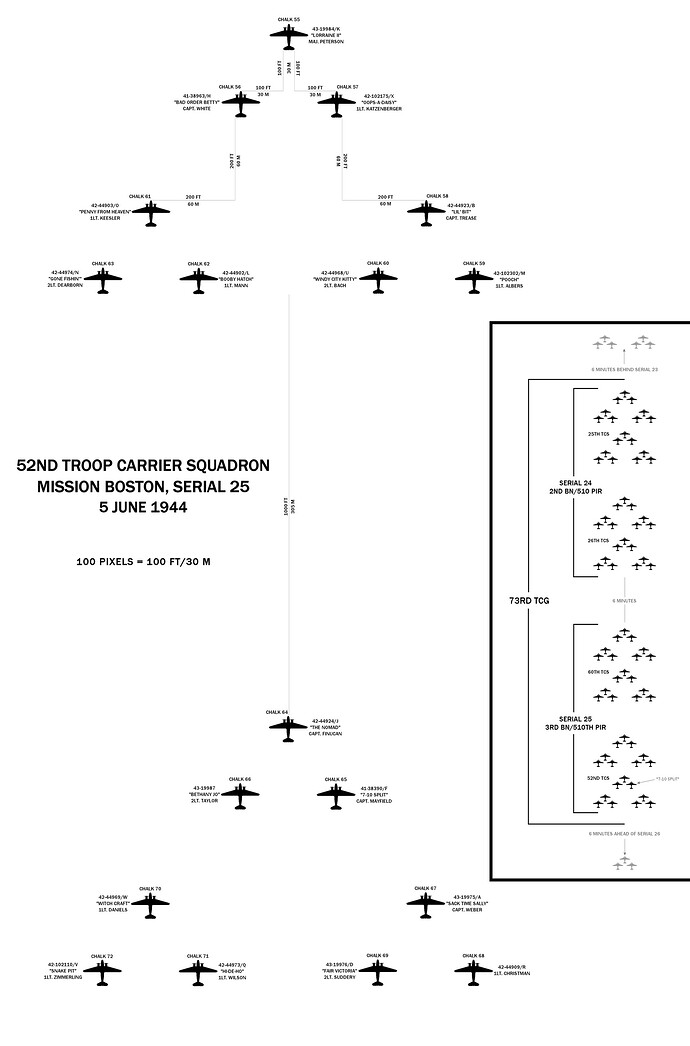

June 6th, 2024, marks the 80th anniversary of the Allied invasion of German-occupied Europe and the beginning of the final destruction of the Nazi Empire. Today we’ll be recreating the 52nd Troop Carrier Wing’s Mission Boston: the overnight transport of the United States Army’s 82nd Airborne Division to Nromandy.

Pee-Wee says: So many airplanes, and crews, and stories! There was no easy way to cover everything in one flight, so I created a fictional unit, with fictional aircraft and crews, and merged various elements of real stories into one. Hopefully this will provide a better idea of what it was like for the men of the Troop Carrier Squadrons that night over Normandy.

We’ll be flying the exact route that one Troop Carrier Group flew on D-Day, starting and ending at RAF Barkston Heath in Lincolnshire. Along the way, we’ll point out of a few sites, but mostly relate details of the journey. Get comfortable: our flight time will be more than four hours!

(By the way, she didn’t just create the unit, but all eighteen individual aircraft, some of the crews, parking and formation diagrams, and even some names of paratroops, all based on real units and real people. Basically, she’s a mega-super-nerd! You’ll get to see her work in the final part of this tour.)

Pee-Wee says: Here’s our ride for today, the magnificently restored C-47 41-38930, named 7-10 Split. She flew with the 73rd Troop Carrier Group’s 52nd Troop Carrier Squadron from her delivery on 7 December 1942 to the war’s end, dropping paratroops in every major airborne operation of the Mediterranean and European Theaters (the only surviving original C-47 that can make that claim). She gained a reputation for being a lucky ship, returning from every mission with barely a scratch, including the fratricide disaster over the Mediterranean in July 1943.

Unfortunately, we don’t have an actual C-47 in MSFS, for reasons I haven’t tried to understand. We’re substituting the Aeroplane Heaven DC-3. Throw me a bone. ![]()

Sergeant Marty Blair, a mechanic assigned to the 52nd in 1943, had been an apprentice artist for an animation studio in California before the war, and painted most of the squadron’s nose art. Our C-47’s normally assigned pilot, Captain George Mayfield, was an accomplished amateur 10-pin bowler and requested “something with a girl and some pins.”

Major Peterson, the 52nd’s commanding officer, immediately denounced Blair’s first iteration as being “risqué beyond even wartime standards of decency” and gruffly ordered it repainted. So, the Sergeant painted a more tame variation which was deemed acceptable. Blair explained that the new girl’s striking resemblance to the good Major’s wife was merely coincidental. ![]()

Thanks again to jamespejam for the custom paint, and to Pee-Wee for creating the nose art!

The Airborne plan for D-Day was simple. The 101st Airborne Division would land on the Cherbourg Peninsula, secure the causeways leading off Utah Beach, and help consolidate the Utah and Omaha beachheads. The 82nd Airborne Division would land further west, secure or destroy bridges across the Douve River to prevent their use by German forces, and protect the entire invasion force’s western flank.

The two Wings of IX Troop Carrier Command would provide more than 800 Douglas C-47s and C-53s to transport 13,000 troops across the English Channel.

The airlift was divided into two missions. The 50th Troop Carrier Wing was assigned Mission Albany and would transport the 101st Airborne to drop zones near Carentan. The 52nd Troop Carrier Wing was assigned Mission Boston and would transport the 82nd Airborne to drop zones northwest of Sainte-Mère-Église. Two missions of towed gliders would follow later in the morning.

Our 73rd Troop Carrier Group was one of six assigned to the 52nd TCW. Stationed at RAF Barkston Heath northwest of Grantham in Lincolnshire, the group was a veteran of North Africa and the Mediterranean and arrived at its new home in February 1944. The Group had four Troop Carrier Squadrons assigned: the 25th (squadron code VC), the 26th (WN), the 52nd (C8), and the 60th (4D).

Pee-Wee says: It’s precisely 11:21 p.m. and the 52nd and 60th Troop Carrier Squadrons’ aircraft are coughing to life on Barkston Heath’s west dispersal pads. The 101st Airborne’s Pathfinders are already heading over the English Channel near Portland Head, and those of the 82nd Airborne are approaching waypoint ATLANTA near Coventry. In just over 90 minutes, the invasion of Europe will begin when the 101st’s 502nd Parachute Infantry Regiment lands east of Sainte-Mère-Église.

7-10 Split’s crew is pilot Captain Mayfield, copilot 1st Lieutenant Lloyd Crocker, crew chief Technical Sergeant Joe Wahl, and radio operator Clyde Pennypacker.

Also aboard the C-47 are fifteen men of 2nd Lieutenant Gerald McGuire’s 2nd Platoon, I Company, 3rd Battalion, 510th Parachute Infantry Regiment: T/Sgt. Blanchett, S/Sgt. Bronkowski, Sgts. Bok and Frasier, T/5 McCaulley, PFCs Chaquette and McMull, and PVTs Block, Bussard, McGrath, Russett, Shelly, Schaeffer, and Simeon.

Six “parapacks” with a combined 2,034 pounds (923 kilograms) of equipment hang from racks beneath 7-10 Split’s belly, and her fuel tanks are filled with 600 gallons of 130-octane. Sitting in the chocks, our girl weighs almost 28,000 pounds.

There are eighty-eight C-47s ready to fly from Barkston Heath: seventy-two mission aircraft and sixteen spares (four from each squadron). Tonight the 52nd Troop Carrier Wing will put 378 aircraft into the air from six airbases using 1,302 pilots, navigators, and enlisted crewmen.

The aircraft will form first into three-ship “V” formations. These “flights” will then be grouped into nine-ship “elements,” which will then be linked like train cars into long formations called “serials.” The 73rd’s four squadrons will makeup Serial 24 (25th and 26th TCSs) and Serial 25 (52nd and 60th TCSs). Only the leaders of each three-ship flight will have navigators aboard.

Having learned hard lessons over the Mediterranean, IX Troop Carrier Command pilots have been practicing night navigation and formation flying for the previous weeks and have nearly perfected the art. The use of specially trained Pathfinder pilots and paratroops to deploy radio and visual markers at each DZ will be critical to the operation’s success. The veteran pilots are confident they’ll be able to land the paratroops on their intended drop zones. All they need is a little luck…and good weather.

Pee-Wee says: Thirty minutes before the squadron’s scheduled takeoff time, Major Peterson begins taxiing Lorraine II from her dispersal, and the other pilots follow in sequence. Captain Mayfield follows his close friend Captain Finucan in The Nomad towards Runway 24. 2nd Lieutenant Taylor in Bethany Jo follows close behind.

At eight minutes to midnight, the first aircraft of Serial 24 roars down the runway and into the darkness. Each serial is allotted six minutes for takeoff. Six minutes for thirty-six aircraft. Ten seconds between takeoffs.

And the crews make it happen.

Pee-Wee says: Serial 25 begins its takeoff at precisely 11:58 p.m. Captain Mayfield follows The Nomad around the corner onto the runway, counts to ten, and calls for takeoff power. Lieutenant Crocker advances the throttles until the two R1830s reach 47 inches of manifold pressure and 2,700 RPM. Weighed down by a payload she was never intended to carry 7-10 Split accelerates far slower than normal. Every rivet and bolt in her fuselage rattles and bangs as she trundles after her sisters.

Crocker calls out airspeeds every ten knots, and most of the runway is gone before he says “eighty.” The overloaded C-47’s tail slowly rises as her speed builds toward ninety miles per hour. At almost one hundred and ten Captain Mayfield pulls gently on the yoke and the terrible racket stops as 7-10 Split rises slowly into the sky. Crocker raises her landing gear and Mayfield follows the rest of the formation–clearly visible under the full moon–into a turn to the east.

It’s 12:03 a.m., 6 June 1944.

![]() ATLANTA: 12:37 a.m. (2 Hours and 1 Minute to Green Light)

ATLANTA: 12:37 a.m. (2 Hours and 1 Minute to Green Light)

Pee-Wee says: Sergeant Wahl sits near the jump door fiddling absentmindendly with his wedding band. The paratroops sit quietly in their metal seats on either side of the fuselage. No one speaks. Private Shelly is airsick.

Sergeant Pennypacker listens to static on frequency 5005. The formation’s radio silence is to be broken only by the Wing Commander, and only in the direst of circumstances. In the cockpit, Lieutenant Crocker scans the engine instruments and listens on VHF for “Sandbag” or “Crowbar,” callsigns that may precede a recall message.

Captian Mayfield is hand-flying, and The Nomad hangs motionless in his windscreen. To his left Bethany Jo is silhouetted against the horizon, her propellers flashing in the moonlight. All is well, and he dares to think “this is going better than Sicily.”

That’s the market town of Rugby sleeping back there. Some of the residents noticed airplanes passing north of town intermittently starting at around 10:20 p.m. and thought nothing of it. But beginning a few minutes before midnight, there were more. Lots more. For the next hour an almost continuous stream of airplanes droned past the town heading southwest. Where they were going was anyone’s guess, but something big was afoot.

Every formation maintains the same altitude and airspeed: 1,500 feet MSL (460 meters) and 140 miles per hour (120 knots, 225 kilometers per hour). There is no radar control. No TCAS. No station keeping gizmos. No NVGs. As long as every formation–every car in an aerial train stretching twenty miles from front to caboose–flies the planned speeds and the planned altitudes, everything will be fine.

![]() CLEVELAND: 1:13 a.m. (1 Hour and 25 Minutes to Green Light)

CLEVELAND: 1:13 a.m. (1 Hour and 25 Minutes to Green Light)

The formation passes several RAF airfields: Melton Mowbray where No. 304 Ferry Training Squadron teaches ATA pilots to fly high performance aircraft, and RAF Honeybourne and its satellite RAF Long Marston where Canadian pilots are being taught to fly the Vickers Wellington by No. 24 Operational Training Unit. Coventry and Birmingham pass on the right, as does Stratford-upon-Avon, birthplace and final resting place of William Shakespeare. A few minutes before reaching CLEVELAND, the formation passes Gloucestershire, home of Gloster Aircraft whose Meteor jet fighter will enter service with the RAF in a month’s time.

Pee-Wee says: The train of C-47s turns south approaching the River Severn estuary. Up ahead are Bristol, Salisbury, Dorchester, and Portland Head where the formation will leave friendly territory. On either side of the formation’s route are the airbases from where Mission Albany launched. The full moon hangs in the sky directly ahead.

Two hundred miles away in Normandy, the 502nd Parachute Infantry has already jumped but is hopelessly scattered in the wetlands and hedgerows. Many paratroops are near their objectives, others are miles away. One hapless stick landed near Couville, twenty miles northwest of the assigned drop zone.

Approximately half of Serial 12 with the 2nd Battalion of the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment aboard is approaching Drop Zone C. The other half is wandering further north, or south, or who knows where. In seven minutes Chalk 67, C-47A 42-100646, will drop her paratroops somewhere northeast of their intended drop zone. She carries fifteen paratroops of 1st Platoon, E Company and their platoon leader, 1st Lieutenant Dick Winters.

![]() FLATBUSH: 1:42 a.m. (56 Minutes to Green Light)

FLATBUSH: 1:42 a.m. (56 Minutes to Green Light)

Pee-Wee says: The formation descends slowly to 1,000 feet MSL (305 meters) over Portland Head. Mayfield and Crocker scan their instruments again, looking for telltale signs of impending failure: high oil temperature, low oil pressure, or fluctuating fuel pressure. 7-10 Split is running fine, as she always has.

Passing FLATBUSH just south of the Portland Bill Light, they descend further to 500 feet (150 meters) above the English Channel. Pilots switch off their navigation lights and dim their formation and cockpit lights. Sergeant Wahl makes certain all cabin lights are extinguished. The formation becomes invisible to radar and prying eyes.

The 101st Airborne’s three Pathfinder serials have returned to friendly territory and are making their way toward RAF North Witham south of Grantham. One aircraft is missing.

Serial 16 is only moments from dropping the last of the 101st Airborne onto Drop Zone D just north of Carentan.

Serial 7 should be approaching FLATBUSH in the opposite direction now, 2,500 feet above Serial 25, heading for home.

Pee-Wee says: Crocker looks up occasionally. The large formations he expected to see passing overhead aren’t there. Instead, he catches glimpses of single ships and the occasional multi-ship flight heading north. He comments about it to Mayfield, and for the first time, the Captain worries.

Serial 17–the first of the 82nd Airborne’s formations–has reached PEORIA, the Initial Point on the west coast of the Cherbourg Peninsula. It will reach the Drop Zone O in ten minutes.

![]() HOBOKEN: 2:06 a.m. (32 Minutes to Green Light)

HOBOKEN: 2:06 a.m. (32 Minutes to Green Light)

Pee-Wee says: Serial 25 reaches HOBOKEN and passes low over the British patrol boat whose Eureka beacon “C” has guided the invasion force across the water. Another turn to the left and the Channel Islands are off the nose. There are occasional dim flashes from over the eastern horizon, and Mayfield thinks again of the straggling formations over FLATBUSH.

As the formation joins the final leg inbound to its Initial Point, the mission is still proceeding is planned. Pennypacker reports the occasional blocking of the command radio channel by a British Broadcasting Corporation station in England. Wahl and the thirty-five other crew chiefs and jumpmasters are making final preparations. Equipment checks. Jump doors open and clear. Lights out.

The 101st Airborne is fully deployed, albeit scattered around the fields and marshes between Sainte-Mère-Église and Carentan. Small groups of paratroops from various units are coalescing and heading toward their objectives. Mission Albany’s aircraft are preparing to land at their bases in the southwest of England, approaching Portland Head northbound, or diverting to the emergency field at RAF Warmwell.

Much of the 82nd Airborne’s 505th PIR is already on the ground near Drop Zone O, and aircraft carrying the 508th PIR are approaching DZ N.

Uknown to the pilots of the 52nd, one C-47 from Serial 19 is already down, and four more from Mission Boston will be shot from the skies in the next ten minutes. Thirteen aircraft from Mission Albany are missing and many more are limping back toward England, shot to pieces and with injured and dead crewmen and paratroops aboard.

Pee-Wee says: Also unknown to the crews, a veil of fog and cloud rising more than 3,000 feet (915 meters) has enveloped the western shore of the Cherbourg Peninsula twenty-three minutes ahead.

![]() The Channel Islands: 2:13 a.m. (25 Minutes to Green Light)

The Channel Islands: 2:13 a.m. (25 Minutes to Green Light)

Pee-Wee says: The formation passes between Alderney to the north and Guernsey to the south. Occasional strings of tracers snake up into the night from both sides and fall fruitlessly into the sea. Airplanes have been passing the Channel Islands since just before midnight. After two hours firing blindly into the night without success, the German gunners must be frustrated.

A few minutes from PEORIA, the lead element begins climbing and slowing and the 52nd follows. At 1,500 feet (460 meters) and 125 miles per hour (108 knots, 201 kilometer per hour), Mayfield becomes aware how sluggish 7-10 Split has become.

She’d been overweight taking off two hours ago and was only now reaching her official maximum takeoff weight. With so much extra weight and the drag of six parapacks hanging from her belly, Mayfield isn’t certain 7-10 Split can slow to the prescribed 110 mph (95 knots, 177 kph) over the drop zone without stalling.

![]() PEORIA: 2:29 a.m. (11 Minutes to Green Light)

PEORIA: 2:29 a.m. (11 Minutes to Green Light)

Pee-Wee says: The formation has reached its Initial Point that marks the beginning of the leg to the drop zone. Mayfield turns on the red signal light and Lieutenant McGuire begins the pre-jump drills his paratroops have practiced hundreds of times. Sergeant Wahl leans out the door and looks forward toward the blacked-out the coast. “Not as distinct as I expected,” he thinks.

The formation crosses PEORIA at 1,500 feet (460 meters). Mission planners believed the threat of balloons over the shoreline was real and thought the higher altitude prudent. Once over land, the formation will descend to 700 feet MSL (215 meters) for the run to drop zone.

Drop Zone T lies astride the Merderet River west-northwest of Sainte-Mère-Église, near Amfreville. The pilots are intimately familiar with the conspicuous bend in the river bordering an open plain, and with the full moon shining, they shouldn’t have difficulty locating the DZ. The Pathfinders’ red-lighted “T” will seal the deal.

Pee-Wee says: The formation is established on the inbound heading now, and Mayfield looks ahead toward the coastline, which seems brighter but less distinct than he expected, and even though the Peninsula is mostly blacked-out by the German occupiers, there is a notable lack of any light on the ground. He is about to comment on the effect to Crocker when The Nomad disappears.

“Uh oh,” he says as the world vanishes into the clouds.

We’ve gone over our ten-screenshot limit again. Sorry about that! We’ll call this the “intermission.”

Pee-Wee says: Stay tuned for Part 2, coming very soon! ![]()