I think part of what your question is getting at is what kind of flying do military squadrons do and what of that can you represent in MSFS as it currently stands. (I’ve been on watch for an exercise with a lot of dead time for the past few days and wrote much out much of this blurb while sitting around while a lot of the rest of the watch team was chit-chatting or doing crossword puzzles.)

I haven’t been in the cockpit for a while, so some of my memory may be rusty, and things will have evolved somewhat between when I last flew and now. While, there’s probably more formal documents on this elsewhere, off the cuff I’d probably be able to group the flying I did into 1) initial training on the aircraft and procedures, 2) proficiency/currency flights, 3) advanced mission and tactics training. (Note that this is from a US Navy perspective, specifically from more tactical aircraft, so while there’s a lot of joint training in the Navy, stuff from different services and countries will likely differ somewhat; anything I talk about here is my own thoughts and not an official statement of the US Navy or US Department of Defense.)

A good reference for some of this I have found is the Chief of Naval Air Training (CNATRA) publications webpage, and I’ll refer to some of these as appropriate. All of the documents there that are not labeled as Common Access Card (CAC) required appear to be cleared for public release and can be read by anybody, and there’s a lot of good reading for any new flyers around here, especially in the ones that say “primary,” instrument, navigation, weather, and so forth: Chief of Naval Air Training | PAT Pubs

I think part of the confusion about military aircraft in a simulation that doesn’t model weapon systems is often due to a lack of detailed knowledge of what’s involved in military flying, a lot of which has overlap with civilian flying. Once you study the material a bit, you can see there is a decent amount of stuff to do. Also, part of it is just having the mental agility to recognize the delta between what is doable in the sim and what can happen in real life and having the ability to either fill it in or hand-wave it with your brain.

So, as far as initial training, whether at the training commands or at a fleet readiness/replacement squadron (FRS) for a combat aircraft, you’ll generally start with learning the basics of the aircraft systems and how to preflight the plane up to various unit-level tactics in formation and everything in between. What this can translate to things to do in MSFS (if the aircraft has at least okay modeling):

1- Basic “buttonology” and systems: like just sitting in the cockpit and going over what does what in the cockpit, and how that extends to how systems interact, e.g. what electrical buses come on with the battery/each engine generator, what’s on each hydraulic system, etc.; if one of the generators goes out, what systems do you lose?

2- Basic procedures: there are checklists and so forth to do through the various phases of flight - start, taxi, takeoff, departure/climb, cruise, descent/approach, landing, taxi, shutdown - and practicing going through all of them helps get your cockpit flow down. This is also where getting used to how the aircraft flies and flying the numbers comes in. (Examples to flip through real quick for an overview in the T-6 Texan II https://www.cnatra.navy.mil/local/docs/pat-pubs/P-764.pdf and the T-45 Goshawk https://www.cnatra.navy.mil/local/docs/pat-pubs/P-1212.pdf )

3- Instrument procedures: your different military aircraft have different navigation systems, and learning how to use those systems and fly those departures and approaches are essential to conducting operations in less than ideal weather and congested airspace. You can go through the whole process of planning out your flight with your flight pubs, write up your DD-175, and actually fly it in the sim. (See https://www.cnatra.navy.mil/local/docs/pat-pubs/P-771.pdf )

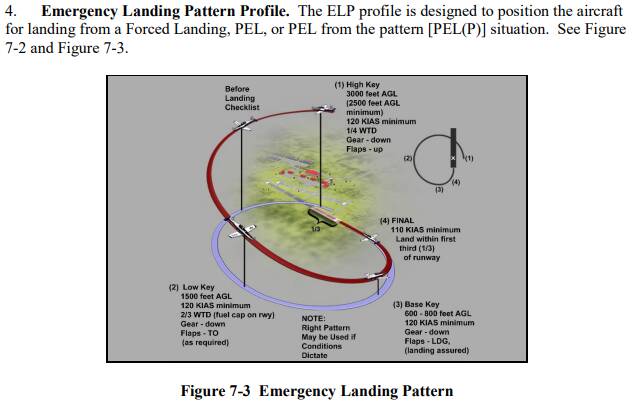

4- Emergency procedures: you can do some degree of practicing various EPs, though it’s obviously limited depending on the level of systems modeling; as in real-life some of the training we can only with any practicality in a simulator, and some things we can do in the aircraft in a limited fashion with some amount of hand-waving. For example, IRL unusual attitude recovery training we can do by having the trainee crew member close their eyes while a/the pilot puts the aircraft in some unusual attitude, and then the trainee has to give direction to recover to the pilot (roll left/right, stop roll, pull, etc.). Otherwise, in MSFS you can try degraded systems by shutting down a HYD switch or turning off an electrical bus, etc. depending on the aircraft. You can also practice emergency landing patterns (simulated engine failure) and so forth.

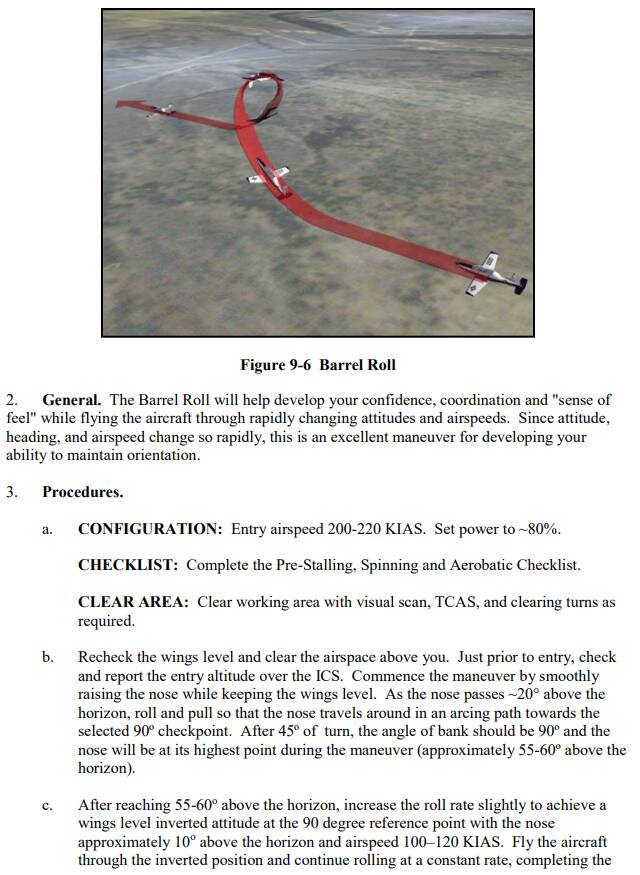

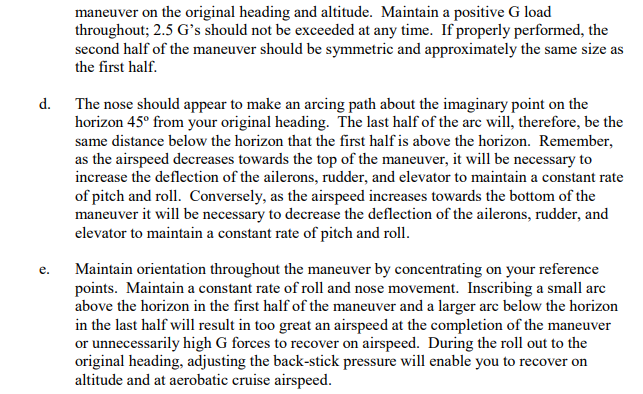

5- Aerobatics: most tactical aircraft have some sort of regimen of aerobatics that provide basic principles that can be extended to various tactical maneuvering. I feel that most non-aviation people don’t have a good sense of aerobatics in that it involves some amount of energy management and precision and isn’t just raging around yanking the stick all over the place.

6- Low level: this is probably the bread and butter of what makes military flying different from civilian flying. While low-level training has tactical utility, much of the purpose of low level training is that it’s one of the most effective ways available in peacetime to conduct training that forces aircrew to learn to perform decision-making and other skills in an environment with stress approaching that of combat.

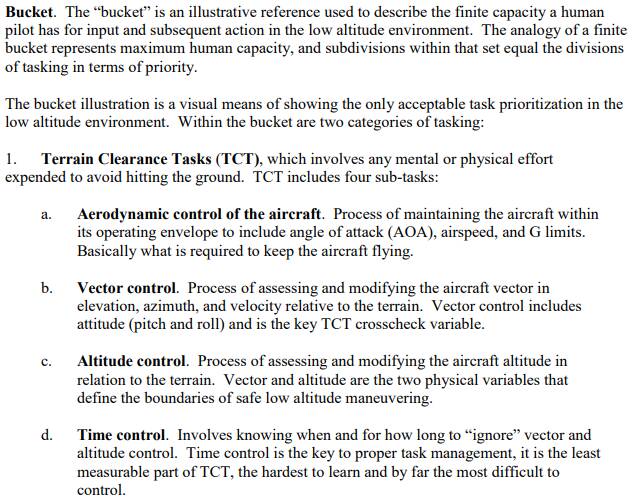

Just to illustrate the decision-making concerns, here’s a snip from the training pub (https://www.cnatra.navy.mil/local/docs/pat-pubs/P-912.pdf ) of the “bucket” model:

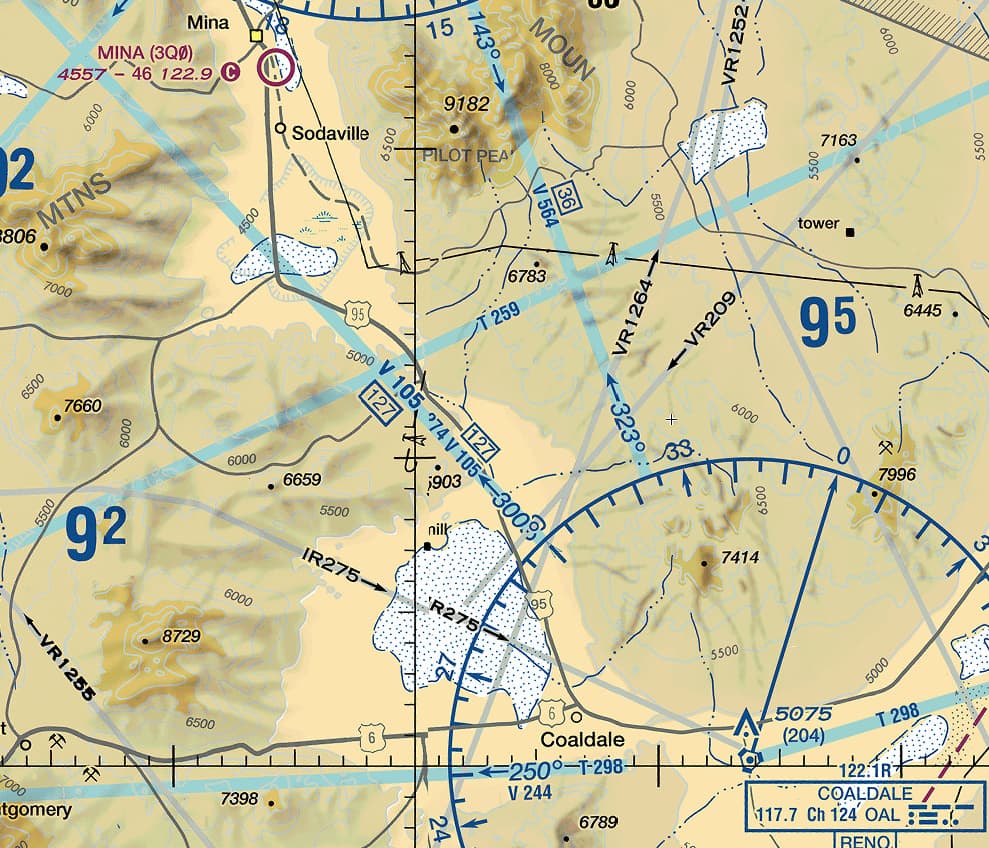

For those who aren’t familiar, here’s a quick primer on how we usually do low level routes. You might have noticed these weird gray lines with arrows going everywhere on section charts (e.g. VR1255, IR275, VR1264, VR209, etc.):

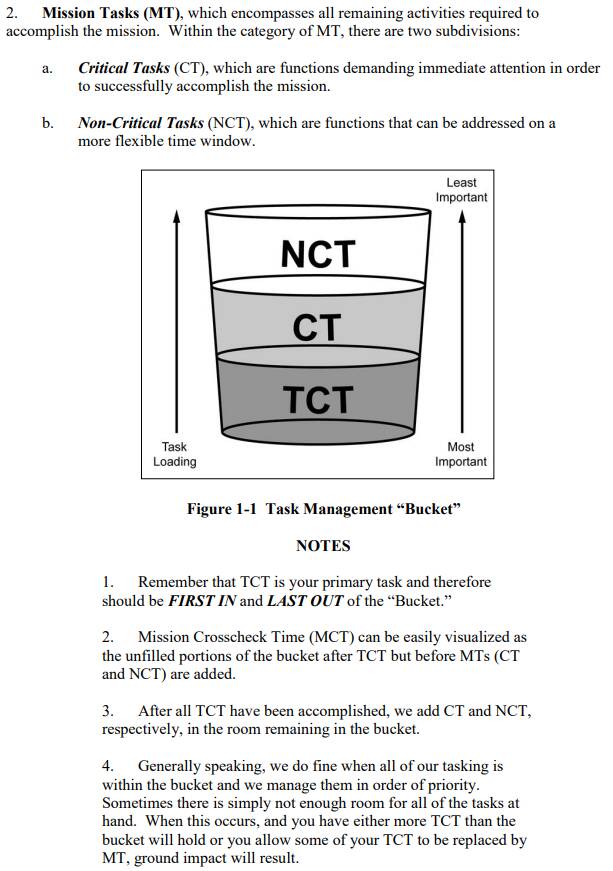

A good starting point, as well as an explanation of those likes, is the AP/1B Area Planning: Military Training Routes pub (https://www.daip.jcs.mil/pdf/ap1b.pdf ). Those lines are various VFR or IFR routes, and here’s a typical entry for one of them in AP/1B; this contains info on the lateral and vertical limits of the route, the controlling agency, any restrictions, etc.:

Usually, you can choose alternate entry and exit points per the notes and don’t have to fly the whole thing, and being scheduled on one of these routes is one of the few ways you can legally fly at way over 250 knots below 10,000 feet. You take this and generate a chart of the route. In the old days, we made them using paper tactical pilotage charts (TPCs), but these days we typically use a software suite called Portable Flight Planning Software (PFPS), primarily one of the apps in it called FalconView. (Image from The Bird’s Eye: Upgrades Mark 20th Anniversary of FalconView Mapping Program | GTRI )

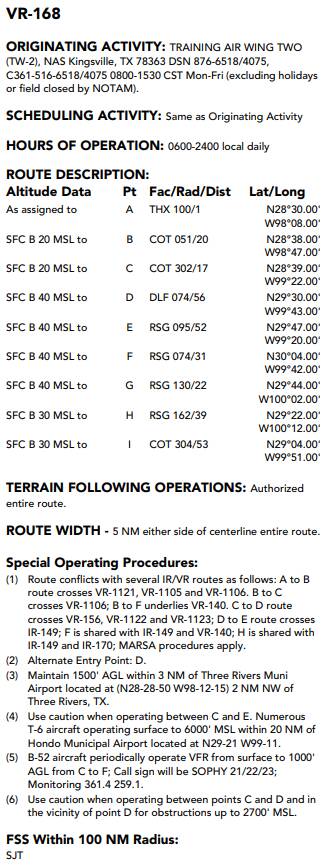

You designate various landmarks to use for timing control that are preferably easily visible visually or on radar. The idea is that you’re calling a certain point along the route (typically your exit point) as the “target,” and you want to get to it at a particular time. This simulates that in real life you would be likely working with other units, and other joint fires would be coordinated so you have a hole over the target when you’re supposed to be there to drop ordnance; being too early or late means you may be flying through friendly artillery shells or missiles. You have to plan your route from the target time back to route entry time, back to takeoff time, and back to engine start time, etc. Typically you would make a strip chart to take in the plan approximately like so (from https://www.cnatra.navy.mil/local/docs/pat-pubs/P-1208.pdf ):

In more modern aircraft, you can load the points in the mission computer or hand jam the lat/longs into the system, but you generally want the chart for your situational awareness and as a backup in case the nav gets degraded. Once you’re flying the route, you have to account for and compensate for wind, which can blow you off course or make your ground speed slower or faster. Being late may mean having to cut off parts of the route (while staying in the AP/1B boundaries) to make back time.

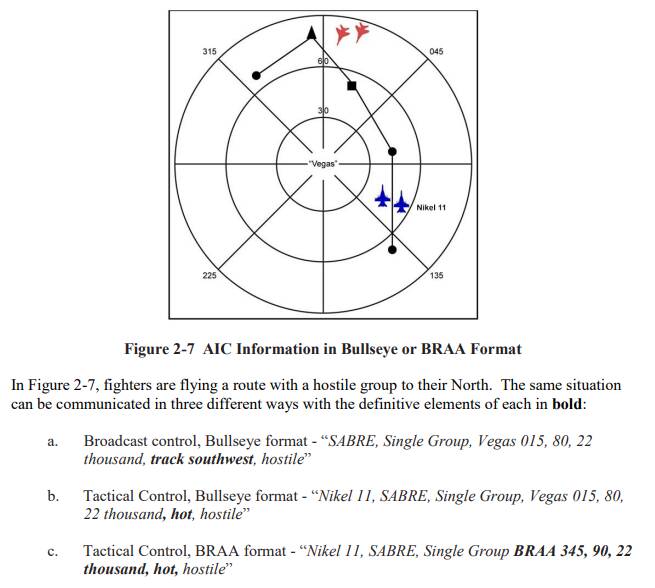

7- Air intercept: This is somewhat harder to do in MSFS as it currently stands, mainly with the current state of multiplayer, but as previously mentioned you can do much of the stuff as long as there’s an interface that allows the participants to see other aircraft and their bearing, range, altitude, etc. (See https://www.cnatra.navy.mil/local/docs/pat-pubs/P-825.pdf)

If they implement some sort of an air traffic control interface at some point (IIRC like they had in FSX), where you could draw range and bearing on a map, you could do most of the stuff up to weapon release and then dice roll the shot results or have a person acting as exercise control evaluate and adjudicate the shots, etc.

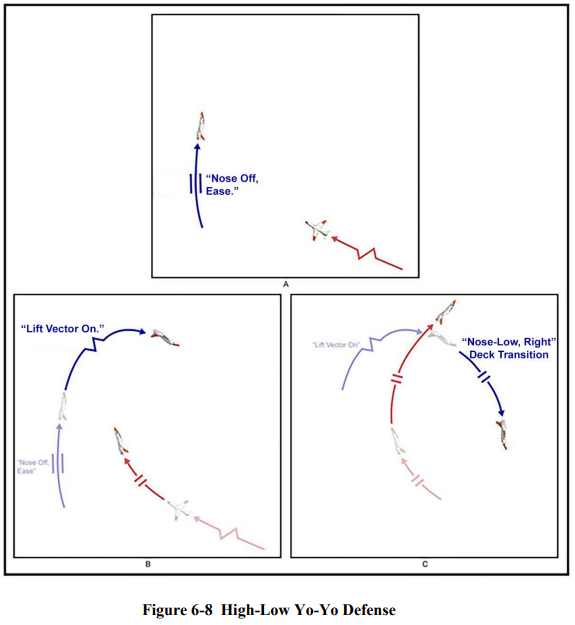

8- Basic fighter maneuvers: BFM is largely done visually, and almost all of the training can be done without actual weapon cuing (primarily going off cockpit sight picture), as the vast majority of is about getting in position to employ a weapon rather than the actual pulling the trigger part. (See https://www.cnatra.navy.mil/local/docs/pat-pubs/P-826.pdf )

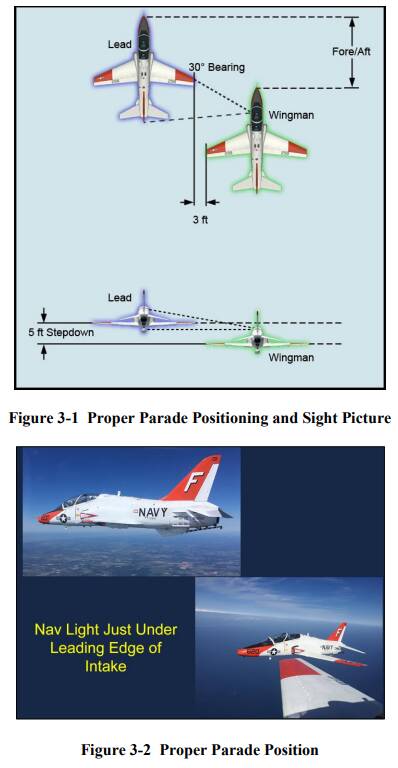

9- Formation: unlike most civilian flying, in tactical military flying you often spend a lot of time operating with one or more wingmen, so (aside the current multiplayer issues) you can practice all of the above with the additional complexity and communications involved with formation flying, including dealing with air traffic control when you have to split off an aircraft from the flight or if one aircraft has an inflight emergency.

As far as proficiency and currency, from my experience a lot of the flying at home station is just maintaining flight hours, instrument time, night time, etc. to maintain certifications/qualifications and basically not get rusty. This is especially important in areas of perishable skills like carrier landings. Much of this involves just getting in the air and doing practice approaches and touch-and-goes. One way squadrons may use some of their training funds is to have aircrews plan and fly cross-country flights, where they will choose some airfield to fly to with various training opportunities near that field or enroute, often with something interesting to do after hours. In those situations, you might be able to practice a few approaches into airfields you haven’t been to before when you make stops for gas, maybe practice air-to-air refueling if you have coordinated with the correct units, fly a low level route for one of the legs, etc. Then you and your crew might get a day off and then do a similar series of things on the way home.

Most of the more advanced tactical training is harder to represent in MSFS as they often get into the specifics of sensor and weapon cueing. In the Navy carrier environment, we do a series of events and unit qualifications and certifications in the “workup cycle” prior to going on deployment. This starts out with unit level training, where the squadron has to meet a minimum requirement of people/aircrews that have completed a syllabus of various training elements, generally including dropping/shooting various weapons and various operational procedures like field carrier landing practice, etc. that are representative of the operational and combat environment. Afterwards, there are training events and exercises with increasingly larger conglomerations of units, e.g. the whole carrier air wing together at NAS Fallon and then with the whole carrier strike group (carrier + air wing + cruiser destroyer group, etc.) off the coast of San Diego. You can represent some of the missions to an extent using combinations of the training methods mentioned previously and a lot of hand-waving, but it might not be that interesting for some missions where systems lack any substantive modeling, such as for electronic warfare aircraft (e.g. EA-18G unless shooting HARM, etc.).

As an additional thought, one of the main things that makes tactical military aircraft “unique” is that many of them have large bubble canopies specifically designed for good all-around visibility that greatly outclasses the visibility from the vast majority of GA fixed-wing aircraft and airliners. This seems to result in a different flying experience in them for many people.