Pee-Wee and Nag and the Ghost Blimp

The Super Spooky Mystery of Blimp L-8

Pee-Wee says: Welcome back, fellow explorers and history buffs! Today’s tour will be a little different, a special installment filled with intrigue, mystery, and physics. Are you ready to hit the airways?

Are you? How’s the wrist?

Pee-Wee says: Meh, not so good. Yes, everyone, I got a little overzealous a few days ago and sprained my wrist, so now I’m all gimpy and wearing a brace that makes doing anything with my left hand difficult. Good thing I’m right-handed! But, sadly…no typing for me today.

That’s alright. You can talk and I’ll transcribe. Care to share how it happened?

Pee-Wee says: No, I do not.

Oh, c’mon. It’s a great story.

Pee-Wee says:  Alright. I was on the way to volunteer at a local food bank when I saw a bus carrying nuns and orphaned puppies being attacked by terrorists, and it was dangling over a cliff and on fire, so I raced over to help, but while I was rapelling down from the ledge, I…

Alright. I was on the way to volunteer at a local food bank when I saw a bus carrying nuns and orphaned puppies being attacked by terrorists, and it was dangling over a cliff and on fire, so I raced over to help, but while I was rapelling down from the ledge, I…

She was rolling over in bed and yawning.

Pee-Wee says: You’re a bum. And please don’t write that.

Okay, I won’t.

Pee-Wee says: Anyway, this tour is something of a passion project of mine. If you’ve been around here long enough, you know that I have a thing for blimps, and I love a good mystery. Today we’ll follow the trail of one of history’s greatest unsolved aerial mysteries: the tale of Navy blimp L-8, the fabled “Ghost Blimp.” (ooooooooooooo  )

)

Yes, she made my type the scary ghost sounds.

Pee-Wee says: We’re very high-tech around here.

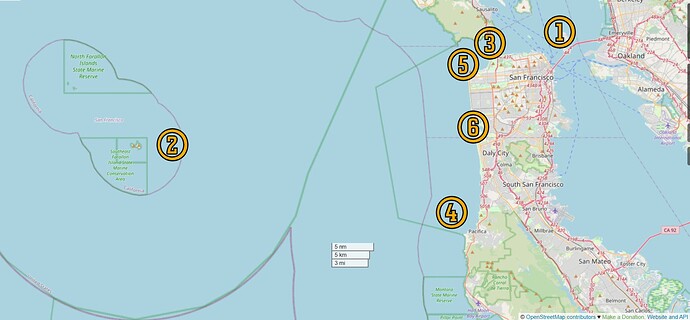

Speaking of high-tech, based on some excellent feedback from a reader and new friend (thanks, Jim!  ), from now on we’ll start each tour with tables showing the closest airports to the tour area, plus all the tour waypoints so that you can create a flight plan before starting to read. This should make following along in real time easier.

), from now on we’ll start each tour with tables showing the closest airports to the tour area, plus all the tour waypoints so that you can create a flight plan before starting to read. This should make following along in real time easier.

Pee-Wee says: Like the format? Don’t like it? Just feel like chatting? PM to let us know!

| Starting Location |

ICAO Identifier |

Distance to First Waypoint |

| Commodore Center (Seaplanes Only) |

22CA |

7.0 NM (13 KM) |

| Oakland International Airport |

KOAK |

9.5 NM (17.9 KM) |

| San Francisco International Airport |

KSFO |

12.5 NM (23.2 KM) |

| Hayward Executive |

KHWD |

16.0 NM (29.6 KM) |

| Waypoint |

Coordinates |

Lat/Long (Skyvector) |

| Treasure Island |

37.8276 -122.3754 |

374941N1222231W |

| Golden Gate |

37.8199 -122.4786 |

374912N1222843W |

| Farallon Islands |

37.6984 -123.0026 |

374154N1230009W |

| The Olympic Club Golf Course |

37.7111 -122.5020 |

374203N1222956W |

| 400 Block East, Bellevue Avenue |

37.7064 -122.4469 |

374222N1222649W |

Pee-Wee says: Now, is everyone ready for a story?

Comfy chair, warm blanket, soft pajamas, milk and cookies. Ready to go.

Pee-Wee says: Can you eat cookies and type at the same time?

sure3. Nop roblenm.

Pee-Wee says: Looks like I’m in good hands.

Pee-Wee says: Before sunrise on 16 August 1942, Navy Lieutenant Ernest Cody and Ensign Charles Adams departed Treasure Island, California for a routine four-hour patrol west of San Francisco aboard Airship Patrol Squadron Thirty-Two’s (ZP-32) blimp L-8. About one and a half hours later, the men radioed their home base at NAS Moffett Field that they were investigating an oil slick near the Farallon Islands, then fell silent. Shortly before noon, the partially deflated L-8 landed on a suburban street in Daly City southwest of San Francisco. All her equipment was present and in working order, and the airship seemed operable.

The only thing missing was the crew. Cody and Adams were never seen again.

The Navy was unable to determine what happened to the two aviators, and the mystery has defied explanation for more than seventy years. Officially their loss is blamed on a freak accident, but there are plenty of alternate theories: the men were taken aboard a Japanese submarine either as prisoners or defectors, or one of the sailors killed the other after quarreling over the same woman before escaping overboard. One theory involves mysterious experimental electronic equipment and a test that went awry. And, yes, some hacks even blame space aliens.

We won’t solve the mystery today, but maybe we’ll shed some new light on the subject. Most of those researching this incident clearly aren’t familiar with aviation and make some incorrect assumptions. We’ll tour L-8’s approximate flightpath and examine the evidence through a pilot’s eyes and highlight some facts that have been overlooked. Along the way we’ll dispel some rumors and also try to answer four questions:

- Why was the blimp allowed to takeoff “too heavy?”

- Why did it take so long for L-8 to reach its first waypoint?

- How did L-8 end up looking like a sad sausage?

- What mysterious electronic equipment was L-8 carrying?

A special thanks to Mr. Otto Gross for gathering documents related to this incident and publishing them online. Unfortunately, his website went dark long ago, and I’ve been unable to find a working email. Wayback Machine to the rescue!

Everyone get ready: this story is pretty long, and it gets pretty deep!

When the United States entered World War 2 in December 1941, the Navy had only ten blimps on hand: three L-Class basic trainers, one G-Class advanced trainer, two former Army general purpose TC-Class ships, and four new K-Class patrol and escort ships. More were planned or being built but wouldn’t arrive for several months.

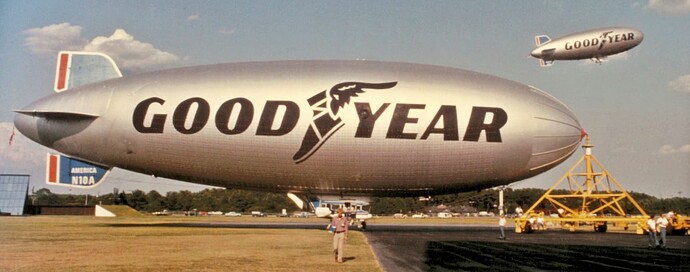

The L-Class was simply Goodyear’s standard pre-war advertising blimp with armament and other military equipment added. As an expediency to bolster the three already in service, the Navy commandeered Goodyear’s five remaining commercial ships in December 1941.

| Designation |

Registration |

Name |

Delivered |

Notes |

| L-1 |

|

|

1938 |

BuNo 1210. Sold to Douglas Sky Advertising in 1952. Fate unknown. |

| L-2 |

NC-10A |

Ranger |

1940 |

BuNo 7029. Destroyed in collision with blimp G-1, June 1942. |

| L-3 |

|

|

1941 |

BuNo 7030. Fate unknown. |

| L-4 |

NC-15A |

Resolute |

1932 |

Returned to Goodyear postwar. Scrapped. |

| L-5 |

NC-16A |

Enterprise |

1934 |

Returned to Goodyear postwar. Rebuilt as N4A Columbia IV. Restored and displayed at Smithsonian’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center, Chantilly, VA. |

| L-6 |

NC-14A |

Reliance |

1931 |

Scrapped. |

| L-7 |

NC-9A |

Rainbow |

1939 |

Damaged at Lakehurst, October 1943. Scrapped. |

| L-8 |

NC-10A |

Ranger |

1942 |

Returned to Goodyear postwar. Rebuilt as N10A America. Restored and displayed at National Naval Aviation Museum, Pensacola, FL. |

Pee-Wee says: There’s some confusion regarding L-8’s identity online, and a careful review of the chart above reveals why! Yes, Goodyear produced two blimps with the same name and civil registration in little more than a year. The original Ranger flew only briefly for Goodyear before joining the Navy as L-2 in February 1941. The second Ranger was built to replace the first but was instead delivered directly to the Navy as L-8 in February 1942 and likely never carried her civil registration or name. She was shipped to NAS Sunnyvale/Moffett Field in Santa Clara, California and first erected in February 1942, then assigned to locally based ZP-32. By August 1942 she had accumulated almost 1,100 hours, averaging approximately six hours airborne every day. Her crews considered her a reliable ship with good flying qualities.

L-8 was instrumental in the success of the Doolittle Raid on Japan. One of the many modifications to the B-25Bs used by the Doolittle Raiders involved swapping part of the bombardier/navigator’s plexiglass window glazing for glass. Unfortunately, the new parts arrived at NAS Alameda several hours after Hornet and the B-25s sailed for the Western Pacific on 01 April 1942. With the carrier’s deck unusable by other fixed-wing aircraft, there was only one type of aircraft that could safely deliver the 300-pound (136-kilogram) load. So, later that afternoon, the parts were airlifted onto Hornet’s forward deck by none other than L-8, flown by ZP-32 pilot Lieutenant Commander John “J.B.” Rieker, a highly experienced Goodyear LTA pilot who volunteered for Navy service.

That’s an odd collection of names for Goodyear’s blimps. What’s that all about?

Pee-Wee says: In 1928, Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company’s President Paul Litchfield, the man who forged the company’s relationship with Luftschiffbau Zeppelin back in 1924, decided that the company’s blimps would henceforth carry the names of victorious America’s Cup sailing yachts. (Reliance, 1903; Resolute, 1920; Enterprise, 1930; Rainbow, 1934; Ranger, 1937) Not counting the Spirit of Akron in 1987, the tradition officially ended in 2005. Today, Goodyear solicits names from its employees and the general public.

Dude, Where’s Our Airport?: Naval Training and Distribution Center Treasure Island

Dude, Where’s Our Airport?: Naval Training and Distribution Center Treasure Island

Pee-Wee says: ZP-32 operated four blimps during 1942: L-4, L-8, TC-13, and TC-14. The larger Army ships operated primarily from Moffett Field while the smaller L-Class trainers–modified with racks for carrying depth charges–flew from forward bases at Treasure Island, Watsonville, and Los Angeles. L-8 flew mostly from Treasure Island, with newly-promoted Lieutenant Cody as the detachment’s Officer in Charge and lead pilot.

It was the confluence of two disparate ideas that brought Treasure Island into existence. In the early 1930s San Francisco’s leaders desired a large airport closer to the city than the existing airport at Mills Field 12 miles (19 kilometers) to the south. At about the same time, the city was planning a large international exposition to celebrate the completion of the Golden Gate and San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridges. The projects were combined: the city would construct an island on the tidal shoals north of Yerba Buena Island that would be used first as an exposition site and then rebuilt as an airport. The Army Corps of Engineers began construction in January 1937 and the Golden Gate International Exposition opened two years later. During the exposition’s second year in 1940, plans were made to transform the island into the new San Francisco Airport.

Pee-Wee says: And then the Navy showed up with an offer the city couldn’t refuse.

The Navy intended to develop a portion of Treasure Island as a departure and receiving center for sailors and marines heading out into the Pacific, but when the shooting started in 1941, the Navy instead created a massive training and personnel/materiel distribution center on the island. An ongoing land dispute with San Francisco was finally settled in 1942 when the Navy seized the entire island. The exposition buildings were transformed into barracks, theaters, training centers, and prisoner of war detention centers, and new instructional centers and support buildings were constructed. A small shipyard–a Frontier Base–was built on the southeast shore near the hangars and docks from where Pan American Airways operated Martin and Boeing Clippers and Consolidated Coranados.

Pee-Wee says: There is a persistent rumor that the Navy swapped Treasure Island for land adjacent to the current San Francisco Airport (SFO). In reality the Navy directly compensated the city for the island by making $10 million (approximately $202 million today) worth of improvements to SFO, including a large landfill project that allowed for much needed runway extensions.

Training and Distribution Center (TADCEN) Treasure Island became a Naval Station (NAVSTA) in 1947 and remained in operation another fifty years. Today, the island is undergoing commercial redevelopment, and former Navy structures are steadily giving way to modern houses, condominiums, and community services. There are currently no homes for sale here, but you can find new condos on neighboring Yerba Buena Island, including a 3 bedroom, 3.5 bath, 2,330 square foot (216 square meter) unit for $3.395 million, or a 1 bedroom, 1 bathroom, 612 square foot (56 square meter) unit for $595,000.

Pee-Wee says: $3.395 million you say? Put me down for two.

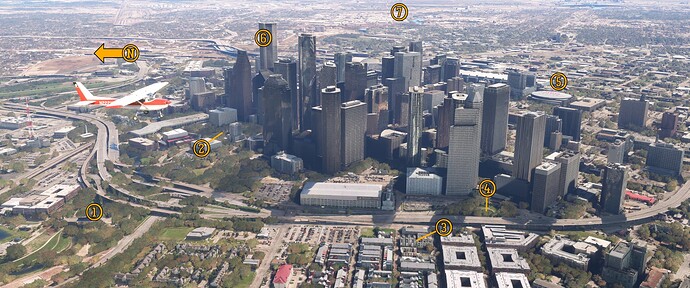

Pee-Wee says: Here we are flying roughly northwest over Treasure Island. That’s the eastern span of the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge in the upper right. Some exposition buildings were intended for future airport use, including the (1) Administration and Terminal Building and (2) aircraft hangars. The new airport’s longest runways would have created a giant “X” across the island but would have been limited to about 5,000 feet (1,520 meters) in length, and Yerba Buena Island and the SFO-OAK Bay Bridge would have obstructed the southern approaches. The “major airport” on Treasure Island was never going to work without serious improvements and landfill.

Any original MythBusters fans here? This (3) is the Treasure Island Sailing Center, where Adam Savage and Jamie Hyneman not only repaired a boat using duct tape, but also constructed a functioning sailboat from the miracle material. Several other early episodes were filmed on TI during the hit television show’s thirteen-year run.

Pee-Wee says: (4) Here’s where the Frontier Base was located. The facility could repair offshore and inshore vessels as large as 2,200-ton destroyers and was staffed roughly equally by military and civilian tradesmen. Many small ships were decommissioned here after the war, and the Frontier Base itself closed shortly thereafter. Today a single pier remains–not one of the originals–although it’s a little “visibility challenged” in MSFS. I really like the name “Frontier Base.” It sounds like something from Firefly or other sci-fi story!

The (5) post office still stands at the corner of 5th Street and Avenue H, and today it’s home to a local moving company and a small auto detailing shop. The laundry and tailoring building still stands to the east across Avenue H in MSFS, but the real building was recently razed.

During the Golden Gate International Exhibition, famed aviator Paul Mantz flew sightseeing tours of San Francisco, Alcatraz, and both of the new bridges from the (6) east seawall dock using a Sikorsky S-38 amphibian. The flights were advertised as “a TRIP ENQUALLED anywhere…the thrill of boating as well as flying.” Almost directly across the street, the U.S. Army displayed its first YB-17 bomber outside the Federal Building and Colonnade of States. The huge bomber landed in the parking lot on the north portion of TI and was towed into position.

Pee-Wee says: (7) The Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES) barracks still stand just up the road from the post office, although it appears their days are numbered. Eighteen WAVES arrived at TI in 1942 and before the war’s end, nearly 800 worked here as physical therapists, nurses, medical orderlies, damage control and firefighting instructors, radio and radar operators, and a myriad of other ratings.

During the exposition, Goodyear’s TZ-Class blimp Volunteer flew from TI for five months, and during the first months of World War 2, ZP-32’s blimps flew from the exposition parking lot using an expeditionary mast and mobile maintenance equipment. One aerial photo shows a blimp (very likely either L-4 or L-8) moored (8) here. We can surmise that on 16 August 1942, this is the exact spot from where L-8 launched on her fateful patrol.

Remember those exposition buildings that were converted into barracks? They stood approximately (9) north and south of this spot. The buildings were never intended for long-term use and were constructed accordingly. In 1947 a fire started in one and quickly spread to the others. The resulting conflagration could be seen from around the bay and threatened to spread across the whole island. Firefighters from nearby communities converged on the island and soon gained control of the conflagration. Thankfully, although forty-one firefighters were injured, there were no fatalities.

Pee-Wee says: That was close! If that fire had happened during the war, the casualties (and the effect on America’s war effort) could have been catastrophic.

L-8 lifted off from Treasure Island about twenty minutes before sunrise on 16 August 1942 with Lt. Cody and Ens. Adams aboard. Aviation Machinists Mate 3rd Class (AM3) James Hill was scheduled to act as the flight engineer, but was removed shortly before takeoff when it was determined the ship was too heavy.

Pee-Wee says: And here’s where the conspiracy theories begin. At the inquest following the incident, ZP-32’s commanding officer and the Ensign commanding the Treasure Island ground party attested that L-8 was 200 pounds (90 kilograms) statically heavy at launch. “What was onboard that made the blimp too heavy, and why would the crew risk flying like that” you ask? Let me explain what “heavy” means in this case. Brace yourselves: I’m going full blimp.

Never go full blimp.

(TLDR: L-8 wasn’t “too heavy” to fly. Seriously, if you find math and physics boring, jump ahead to  . No judgement here!)

. No judgement here!)

Blimps use two types of lift to fly: static and dynamic. Static lift is generated by the difference in density between the lifting gas within the blimp’s envelope and the surrounding atmosphere (i.e. buoyancy), just like a hot air balloon or helium-filled party balloon. At any given time, blimps are either statically heavy, neutral, or light. A statically heavy blimp weighs more than its static lift and will sink, while a statically light blimp weighs less than its static lift and will rise. On the morning of 16 August, L-8 was statically heavy, which is not an abnormal condition. In actual fact, according to the squadron commander’s testimony, ZP-32’s L-Class blimps could operate up to 600 pounds (272 kilograms) statically heavy. The confusion likely comes from attempting to correlate a blimp’s static heaviness to an airplane being overweight.

How much static lift could an L-Class blimp produce?

Pee-Wee says: Stand back…she’s going to math! The L-Class blimp envelopes had a theoretical maximum volume of 123,000 cubic feet (3,483 cubic meters). Navy LTA manuals state that each 1,000 cubic feet (28.3 cubic meters) of Helium gas can lift 62 pounds (28.1 kilograms). Therefore: 123,000 cubic feet of Helium gas x 62 pounds per 1000 cubic feet = 7,626 pounds of static lift.

That doesn’t seem like much from such a large envelope, does it?

Pee-Wee says: It isn’t, and that’s gross lift, not useful lift. If you want to know how much “stuff” you can carry, you’d have to subtract the weight of the blimp itself, which we unfortunately don’t know. James Shock, author of U.S. Navy Airships, says the L-Class had a useful static lift of only about 2,000 pounds (907 kilograms).

So, how does a statically heavy blimp takeoff and why doesn’t it just sink back to the ground like an old party balloon?

Pee-Wee says: That’s exactly what would happen if it weren’t for the second type of lift. Dynamic lift is generated by aerodynamic forces on the blimp as it moves through the air, usually by increasing the blimp’s angle of attack. The effect is dramatic: a K-Class blimp travelling at 20 knots (37 kilometers per hour) with an angle of attack of 10 degrees generates approximately 1,400 pounds (635 kilograms) of dynamic lift against a useful static lift of about 8,000 pounds (3,629 kilograms). A statically heavy blimp must make up for its “heaviness” by making a running takeoff like an airplane or getting a boost from its ground crew. Again, this is a normal situation.

Some people say that L-8 was heavy because of secret equipment it was carrying, and that the crew wouldn’t have allowed the blimp to fly “too heavy.” You’re saying that’s bogus.

Pee-Wee says: Yup. Later in his testimony, the squadron commander states that morning flights usually carried two crewmembers, while afternoon flights subject to superheating carried three. Superheating occurs as the sun warms the helium, reducing its density and increasing the blimp’s buoyancy, generally by about 1% for every 5 degrees Fahrenheit (0.5 degrees Celsius). So, it was completely normal for one crewmember to be left behind on a morning flight.

What about the dew? Some reports indicate that AM3 Hill was left behind because of the extra weight of water on L-8’s envelope. Does water really weigh that much?

Pee-Wee says: Oy. Now we’re into elliptical math. You’re up, Einstein. I’m going to find some Tylenol.

Okay, here’s an exceptionally rough calculation. An L-Class blimp’s envelope had a surface area of approximately 7,000 square feet (651 square meters). Let’s assume approximately one third of that–2,400 square feet (223 square meters)–was covered by dew 0.02 inches (0.5 millimeters) thick. At 60 degrees Fahrenheit (15.5 degrees Celsius), that water weighs approximately 250 pounds (113 kilograms).

Pee-Wee says: An average Navy LTA crewman weighed 175 pounds (79 kilograms), so having Hill aboard would have made L-8 almost 400 pounds (182 kilograms) statically heavy. I don’t have access to any performance information for L-Class blimps, so we’ll demonstrate with a similar ship again. A K-Class blimp 200 pounds heavy and with zero headwind needed about 600 feet (183 meters) to become airborne using the rolling takeoff technique. At 400 pounds heavy that distance jumped to 1,100 feet (335 meters). Looking at period aerial photos, L-8 had barely 1,000 feet (305 meters) available for a running takeoff. So, there’s nothing mysterious about Lt. Cody’s desire to be 200 pounds statically heavy instead of 400 at takeoff. It would have been unnecessarily difficult to create that much dynamic lift in the distance available for takeoff. So…enjoy your day off, Mister Hill!

And none of this was abnormal.

Pee-Wee says: Not according to the testimony of multiple professionals involved. It’s just the nature of blimp operations before the development of modern airships with vectoring thrust and other innovations.

But why did they leave Hill behind and not Adams, who wasn’t even a qualified pilot?

Pee-Wee says: Let’s keep going and find out.

Where’s Michael Bay When You Need Him?: The Golden Gate Bridge

Where’s Michael Bay When You Need Him?: The Golden Gate Bridge

Ten minutes after takeoff, L-8 soared over the Golden Gate Bridge. It’s hard to imagine a time when this magnificent structure didn’t guard the entrance to San Francisco Bay, but in August 1942, it was only five years old.

Pee-Wee says: According to some completely unofficial, unverified, and highly tongue-in-cheek online records, the Statue of Liberty has been destroyed more times in films than any other landmark. The Golden Gate Bridge comes in second. Where’s “director” Michael Bay when you need him?

Here we are flying west toward the Golden Gate. (To clarify for non-locals, the Golden Gate is the narrow strait connecting San Francisco Bay to the Pacific Ocean. The Golden Gate Bridge spans the Golden Gate.) Marin County is on the right, and San Francisco lies just beyond the left edge. It appears that Point Bonita in the distance is having some display issues! The Golden Gate is approximately one mile (1.6 kilometers) across, and until 1967 the Golden Gate Bridge was the longest and tallest suspension bridge in the world.

Pee-Wee says: As Cody and Adams approached the Golden Gate, the rising sun probably caused the tops of the support towers and the clouds beyond to glow. What a sight that must have been!

Pee-Wee says: Why did AM3 Hill get off L-8 and not Ens. Adams? We don’t know for certain, but there are some clues.

Lieutenant Cody joined the Navy in 1932 and served two years as an enlisted sailor aboard the battleship Tennessee until receiving an appointment to the United States Naval Academy. He graduated in 1938 and returned to sea aboard the cruiser Milwaukee and destroyer Biddle before heading to NAS Lakehurst for LTA pilot training. Cody was designated a naval aviator in December 1941 and reported to ZP-32 at NAS Moffett Field. He was 27-years-old and lived with his wife, Helen, in Santa Clara. His logbook tallied approximately 760 total flying hours, with nearly 400 in L-Class blimps, most of those in L-8.

Ensign Adams joined the Navy in the early 1920s and served nearly his entire career with Navy LTA. He was a coxswain aboard Los Angeles until its decommissioning in 1932, served briefly as a boatswain’s mate aboard Akron before her fatal crash in 1933, and survived the Macon’s crash near Monterey Bay in 1935. Back at Lakehurst, he was commended for rescuing passengers and crew of Hindenburg when the German airship crashed there in 1938. Having previously advanced to warrant officer, he was commissioned an Ensign only the day before the incident. Thirty-eight-year-old Adams also lived in Santa Clara with his wife, also named Helen, and had logged almost 2,300 hours aloft, all in rigid airships.

While neither officer was considered inexperienced, Adams was the more senior and more experienced LTA man, but Cody was the more experienced blimp crewman.

Pee-Wee says: According to the squadron C/O’s testimony, Adams was expected to attend LTA pilot training and was completing a series of familiarization flights with ZP-32, including the flight aboard L-8 on 16 August 1942. We can draw the conclusion that, when it was determined that one crewman must remain behind, Cody had the choice between Hill, a freshly-enlisted mechanic, and Adams, a twenty-year veteran with experience in all manner of jobs aboard airships.

And considering L-8 was a reliable ship and the mission was likely expected to be a “milk run,” Cody decided to allow Adams to complete his familiarization flight and booted Hill overboard.

Pee-Wee says: That’s my guess, too. There’s no record outlining Cody’s decision so we’ll never know for certain.

That seems to be a recurring theme with this incident.

Pee-Wee says: Yes, but wait! There’s more!

The Islands of Misfit Scenery: The Farallon Islands

The Islands of Misfit Scenery: The Farallon Islands

Pee-Wee says: After clearing the Golden Gate, L-8 proceeded along its normal morning patrol route toward the Farallon Islands 31 nautical miles (56 kilometers) west of Treasure Island. Normally the blimp would have then flown north to Point Reyes, south to Montara Beach, and finally back north to the Golden Gate. But on 16 August, at 7:38 a.m., Cody and Adams reported they were four miles east of the Farallons and investigating an unusual oil slick. That message would be the last communication with L-8 and her crew.

As soon as Pee-Wee pulled me down this rabbit hole, something about the timeline seemed curious. L-8 departed Treasure Island at 6:03 a.m. and was four miles east of the Farallons at 7:38 a.m., one hour and thirty-five minutes after takeoff (Some reports say the radio call came at 7:50 a.m. We’re sticking with the squadron C/O’s original time from the inquest). The L-Class blimps cruised at 43 knots (80 kilometers per hour). At that speed, L-8 should have arrived over the oil slick approximately 38 minutes after takeoff, or 6:42 a.m. Even accounting for a 10-knot (5.2-meters per second) headwind, they should have arrived at 6:52 a.m. Clearly Cody and Adams were not flying at normal cruise speed or were following a meandering course. What were they doing?

We know they were maneuvering to observe sea traffic, and the two men were likely discussing Adams’s experiences aboard the Navy’s rigid airships. But remember that Adams was aboard to familiarize himself with blimp operations. Cody very likely allowed Adams to fly and “get a feel for” the airship since, having started his LTA career as a coxswain steering Los Angeles, Adams was not unfamiliar with piloting an airship. It’s hard to “get a feel for” an aircraft while flying in a straight line at a constant speed.

Pee-Wee says: At 7:38 a.m., one of the airmen radioed the L-8s’s position, and four minutes later stated that they were investigating an oil slick. According to sailors aboard nearby commercial and military ships, L-8 remained in the area until it dropped two smoke flares and climbed up into the overcast. The eyewitnesses were unable to say definitively whether the ship was under control.

Pee-Wee says: So…here we are flying west over…uh…Southeast Farallon…maybe. It appears some sort of nuclear apocalypse happened here, or perhaps Asobo didn’t allow the dough to rise. Regardless, now that you’ve seen what the islands look, you don’t need to waste time flying out here unless you really want to. You’re welcome!

Is that…a black hole?

Pee-Wee says: That’s Seal Rock. Look closely and you’ll see that there’s terrain there, just no texture. (1) Main Top Island–where the Liberty ship Henry Bergh wrecked in 1944–lies to the left of the very narrow (2) Jordan Channel barely visible in the narrow isthmus running to (3) Southeast Farallon. The Farallon archipelago is about 12 miles (19 kilometers) long and consists of four island groups: Southeast Farallon, Middle Farallon, North Farallon, and Fanny Shoal/Noonday Rock. Some mariners still refer to the islands as the Devil’s Teeth for their propensity for chewing into the hulls of ships that wander too close. Only Southeast Farallon is inhabited, by Point Blue Conservation Science and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service researchers.

The U.S. Lighthouse Service established the first order Farallon Island Light atop (4) 246-foot (75 meter) Tower Hill on Southeast Farallon in 1855 (its ruins should be visible just ahead of our Stearman, but…oh well). Fifty years later the U.S. Navy constructed a high-frequency direction finding station on the plain below. The station was initially used for navigational assistance but provided valuable signal intelligence (SIGINT) during World War 2 as part of the Navy’s Pacific Net. Other PacNet stations were located at Imperial Beach and Point St. George, California; Bainbridge Island, Wahington; and Sitka, Alaska.

We found two independent sources referencing a “secret radar station” on Southeast Farallon or Maintop Island during World War 2, including a photo purportedly looking down on the station from Tower Hill. Unfortunately, we weren’t able to find any reliable information about the rumored station, and there isn’t anything identifiable as a period radar in the photo. We’re not saying there wasn’t a radar station on the Farallons, we just can’t find any information about it, which seems a little suspect.

Pee-Wee says: Any environmentalists reading should probably skip this next paragraph.  From 1946 until 1970 the United States dumped more than 47,000 steel drums containing laboratory radioactive waste at two sites southwest of the Farallons, the closest being only 8 miles (13 kilometers) away. Years later, experts determined that removing the rusting barrels would likely spread the contamination, and they were left in place. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, most of the material has decayed by now.

From 1946 until 1970 the United States dumped more than 47,000 steel drums containing laboratory radioactive waste at two sites southwest of the Farallons, the closest being only 8 miles (13 kilometers) away. Years later, experts determined that removing the rusting barrels would likely spread the contamination, and they were left in place. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, most of the material has decayed by now.

The Navy’s light carrier CVL-22 Independence rests about 14 miles (23 kilometers) south of Southeast Farallon. Having survived World War 2, Independence was used in the Crossroads Able and Baker nuclear tests in 1946. She sustained severe damage and received high doses of radiation and was later towed to San Francisco Bay for decontamination experiments before being scuttled by naval gunfire.

From the Farallons, L-8 would have turned north toward Point Reyes. What actually happened is unclear, and we have only a few data points from the official inquest. According to the squadron C/O:

- L-8 departed Treasure Island at 0603 local time.

- The blimp was four nautical miles (7.5 kilometers) east of the Farallons between 0738 and 0742 local time. We presume this means Southeast Farallon, the only island readily identifiable from a distance at low altitude. Eyewitnesses aboard ships nearby reported that the blimp remained in the area until approximately 0900, and possibly as late as 0945, although those times are unverified.

- The pilot of a Pan Am Clipper over the Golden Gate Bridge reported sighting the L-8 at 1049. It is unclear whether the reporter meant that he or the blimp was over the bridge.

- A Navy OS2U patrol plane reported that L-8 was three nautical miles (5.5 kilometers) west of Salada Beach (known today as Sharp Park Beach) at 1100, reportedly above a solid overcast cloud layer.

- An Army P-38 fighter reported that L-8 was near Mile Rock two nautical miles (four kilometers) outside the Golden Gate at 1105.

- A Navy enlisted man reported the misshapen L-8 was over land “south of San Francisco” at 1115. The squadron C/O received another report that L-8 landed at Fort Funston approximately six nautical miles (11 kilometers) south of the Golden Gate very shortly after the previous report.

OpenStreetMaps

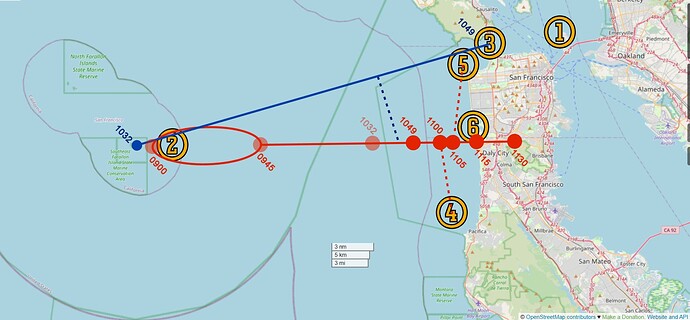

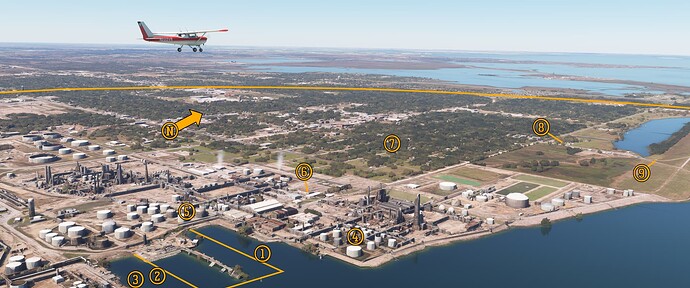

Pee-Wee says: So, here’s the big picture as initially reported, and it’s just a mess. (1) Here’s Treasure Island. We know it took about an hour and a half for L-8 to reach (2) the point four miles east of the Farallons, and she remained in this area until 0945 at the latest. She was next sighted by the Pan Am crew (3) “over the bridge” at 1049, (4) west of Salada Beach eleven minutes later, (5) over Mile Rock five minutes after that, and (6) near Fort Funston at 1115. She settled to the ground in Daly City at approximately 1130.

Let’s calculate the speeds necessary to reach those points at those times. If L-8 departed the Farallons at the latest time (0945), she needed a ground speed of 21 knots to reach the Golden Gate Bridge at 1049.

That sounds reasonable if she was under power or drifting with a strong westerly wind.

Pee-Wee says: Yes, it does. But to then reach the spot off Salada Beach at 1100 would require a ground speed of 67 knots.

Which is faster than L-8’s reported maximum design speed. And she’d be drifting into the wind, too.

Pee-Wee says: Now hold on to your hat. To reach Mile Rock at 1105 would require a ground speed of 125 knots.

That’s one fast blimp.

Pee-Wee says: This is why eyewitness reports–even those from highly trained people–are always suspect. There’s so much “slop” in these position reports that it’s hard to take them at face value. Why the obvious errors, and which reports are correct? The Navy OS2U and Army P-38 were above an overcast layer, which would make identifying specific landmarks difficult and explain their errors.

Sometime between 9:30 and 10:00 a.m. the Navy transmitted a radio message to all ships and aircraft in the area seeking information regarding the missing blimp. When that message was transmitted, the Pan Am Clipper inbound from Honolulu would have been nearly 100 nautical miles (185 kilometers) west of the Golden Gate and possibly outside reception range. The crew may have seen L-8 and thought nothing of it until they made contact with the Pan Am station at Treasure Island and finally received the message. They may have reported seeing the blimp when they crossed over the Golden Gate Bridge at 10:49 a.m., but with the report passing through a literal “game of telephone” before reaching the ZP-32 squadron C/O, it’s easy to see how it could have been morphed into “L-8 was over the bridge at 10:49.”

Pee-Wee says: What if we consider two known locations and times and plot a theoretical course from there? We know for certain L-8 made landfall near the Olympic Club golf course at about 1115 and landed in Daly City fifteen minutes later. From that, we can calculate an approximate ground speed: 10.3 knots. From that, we can deduce the following scenario:

OpenStreetMaps

The solid red line indicates L-8’s approximate course, assuming a steady drift from its location near the Farallons to Daly City at 10.3 knots. For L-8 to reach Daly City at 1130, she would have started somewhere within the oval between the two faded dots labelled “0900” and “0945,” the time window within which she was last seen from nearby ships. The dashed red lines show the lines of sight from the (4) OS2U west of Salada Beach and the (5) P-38 over Mile Rock to L-8’s proposed position. The blue line indicates the approximate path of the Pan Am Clipper. The airplane’s flightpath may have taken her directly over Southeast Farallon at about 1032, and the L-8’s proposed position at that time is shown by the faded red circle labelled “1032.”. The blue dashed line indicates the line of sight from the Clipper to L-8’s proposed position between 1040 and 1045, when the airliner would have been closest to the drifting blimp.

Long story short: this scenario assumes Cody and Adams exited the L-8 from their last known position east of the Farallons sometime around 0900. If they left the ship earlier, a slower groundspeed would be required, but the path would be the same. We’ve made numerous assumptions based on questionable reports here, but this scenario is plausible based on the facts at hand.

Pee-Wee says: Let’s continue on to the beach where L-8 first landed.

Putting From the Deep Rough: The Olympic Club Golf Course

Putting From the Deep Rough: The Olympic Club Golf Course

At approximately 11:15 a.m., two men swimming off the beach below the Olympic Club Golf Course watched L-8 drift in low over the surf, her engines silent and her mooring lines dragging the water. They attempted to wrangle the wayward airship to no avail, and she continued inland, crashing up the cliff face. One of the ship’s Mark 17 depth charges was dislodged by the impact and landed harmlessly on one of the fairways. Freed of the extra weight, L-8 rose into the sky again and drifted east toward Daly City.

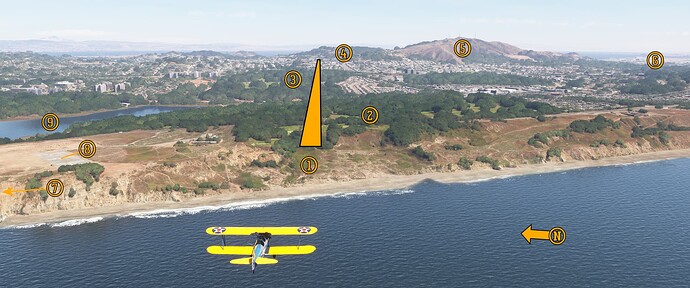

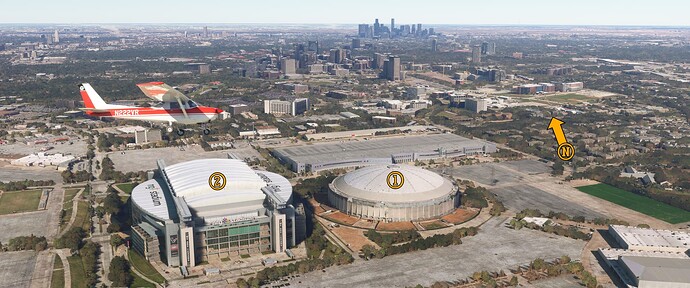

Pee-Wee says: Here we are flying east along the L-8’s probable route toward Daly City. The airship first landed somewhere on the (1) sandy cliffs below the (2) Olympic Club’s 18-hole Lakeside and Ocean Golf Courses. One eyewitness stated that L-8 followed a narrow valley up into the cliffs. The only “valley” we could find is just to the left of (1). L-8 rose higher into the sky and drifted over the neighboring (3) San Francisco Golf Club. In the distance are the (4) Crocker Hills where she eventually landed, (5) San Bruno Mountain, and (6) San Francisco International Airport. (7) Fort Funston lies off the left edge of the photo, north of Nike surface-to-air missile site (8) SF-59L, which lies on the western edge of (9) Lake Merced.

The Olympic Club was founded in 1860 and is the oldest athletic club in the United States. The neighboring and financially troubled Lakeside Golf Course was purchased in 1917 and became the Ocean Club’s Lakeside course. Routinely voted one of the finest golf clubs in America, the Ocean Club has hosted numerous championships, including five U.S. Opens and one Women’s U.S. Open. The San Francisco Golf Club behind is considered one of the most exclusive members-only golf courses, with some of its members ranked with the richest people in the world.

Pee-Wee says: Both clubs were “gentlemen only” until 1990 when, rather than face legal judgment in a pending lawsuit, the Olympic Club admitted women. The San Francisco Golf Club remains closed to the fairer sex.

In August 1942 the San Francisco Airport was an Air Transport Command port of embarkation for troops and other personnel heading into the Pacific Theater of Operations. The collocated Coast Guard Air Station San Francisco opened in 1941 and remains the airport’s longest tenured resident.

Pee-Wee says: Fort Funston was a coastal defense battery built during World War 1 and named for Congressional Medal of Honor recipient General “Fighting Fred Funston.” In 1906 Funston was stationed at The Presidio and used his troops to protect San Francisco from looters, establish communications, sanitation, and medical stations, and return the city to order following the historic earthquake and fire. While he was lauded at the time, modern historians acknowledge that many of his efforts were ineffective or resulted in the further destruction of property and the murder of innocent civilians. Fort Funston eventually mounted numerous heavy artillery pieces, including 6-inch (155-mm) cannons intended for navy battleships cancelled after World War 1. The battery closed in 1963 and is today protected by the National Park Service.

Fort Funston entered the missile age in 1959 when Nike missile site SF-59L (“San Francisco Site 59–Launcher”) became operational. The site–one of twelve that defended the Bay Area–was inactivated four years later, and today it serves as the parking lot for the hang-gliding area here. The former launcher doors are clearly visible in the current Google Street View. The former barracks and operational buildings have been repurposed as the San Mateo and Ocean District Ranger Station.

Back to our wandering blimp, and…oh boy…

Pee-Wee says: Yup. Physics, incoming!

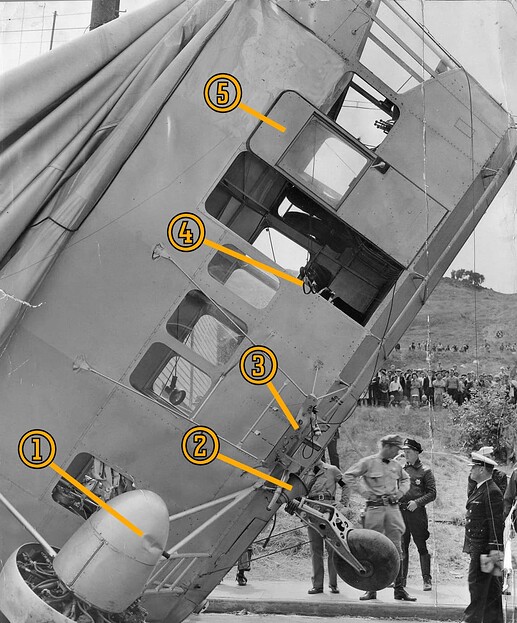

Here’s a famous picture from the National Archives showing L-8 drifting backwards over Daly City. Her pendant number was painted over and the red, white, and blue stripes removed from her rudders earlier in the summer of 1942, although she still carries the U.S. flag on her stern. The port-side Mark 17 depth charge is visible just below and in front of the port engine.

Pee-Wee says: How did she end up in this condition? Let’s go back to static lift. L-8 departed Treasure Island 200 pounds (91 kilograms) statically heavy. In his testimony the ZP-32 squadron C/O said he expected L-8 to become statically neutral at approximately 7:30 a.m. How does an airship go from heavy to neutral in flight? By burning fuel. AvGas weighs six pounds (2.7 kilograms) per gallon (3.8 liters), and at its normal cruising speed, L-8 burned 12 gallons (45.4 liters) per hour. So, between the blimp’s takeoff at 6:03 a.m. and 7:30 a.m., she would have burned about 18 gallons (68 liters) of fuel, or about 108 pounds (49 kilograms).

That’s still not equal to the 200 pounds (91 kilograms) static heaviness.

Pee-Wee says: The remainder comes from superheating of the helium by the rising sun and other atmospheric conditions, all of which increased the ship’s static lift. I have no way to prove his calculation, but the squadron C/O was an experienced LTA pilot, and I trust his answer. Therefore, when Cody and Adams made the radio call at 7:38 a.m., L-8 should have been statically neutral.

Witnesses reported watching L-8 maneuver over the water, drop smoke flares, and then climb up into the overcast. If, as the Navy believes, Cody and Adams fell overboard in a freak accident, would that make L-8 suddenly statically light?

Pee-Wee says: It sure would. Using the Navy’s standard weights, both men going overboard would remove about 350 pounds (159 kilograms) total from the blimp, which would likely cause L-8 to rise rapidly upward to her pressure height.

Pressure height?

Pee-Wee says: As a blimp–or any balloon for that matter–rises higher into the atmosphere, the ambient pressure decreases while the lifting gas’s pressure remains about the same, causing the envelope to stretch. Too great a pressure differential could cause the envelope to tear. The altitude to which a blimp can climb without risking damage is its pressure height. To climb above that altitude, the blimp must reduce the pressure inside the envelope. On 16 August, L-8’s pressure height was about 2,100 feet (640 meters), according to the C/O’s testimony.

The pressure can be reduced by manually venting helium, but that’s wasteful. Instead, blimp envelopes contain ballonets, smaller envelopes which are filled with ambient air to help trim the blimp and control pressure within the envelope. If the pressure in the envelope becomes too great, the air inside the ballonets can be vented, shrinking the ballonet and giving more volume for the helium, thereby decreasing the pressure. All airships also have safety valves that will automatically vent the lifting gas if the internal pressure becomes too great. Since neither Cody or Adams were aboard to control helium venting or the ballonets, L-8 simply climbed until the automatic vents opened, then descended again.

Normally, the ballonets could have been pressurized with ambient air to make up for the loss of pressure, but that would have required both crew intervention and the engines to be running. (See the two “tubes” sticking down from the envelope behind the engines? Those are the intakes through which the propeller wash pushed air into the ballonets.) With her helium severely depleted and her ballonets empty, L-8’s envelope didn’t have enough internal pressure to maintain its shape, and the weight of the control cab caused the ship to sag in the middle.

And having vented helium, L-8 settled back down below the overcast and ran up onto the cliffs near the golf course.

Pee-Wee says: Yes. Now, please remember that these explanations are simplified, and I’m no LTA pilot! Flying an airship is far more complicated than it sounds.

There Goes the Neighborhood: 400 Block East, Bellevue Avenue, Daly City

There Goes the Neighborhood: 400 Block East, Bellevue Avenue, Daly City

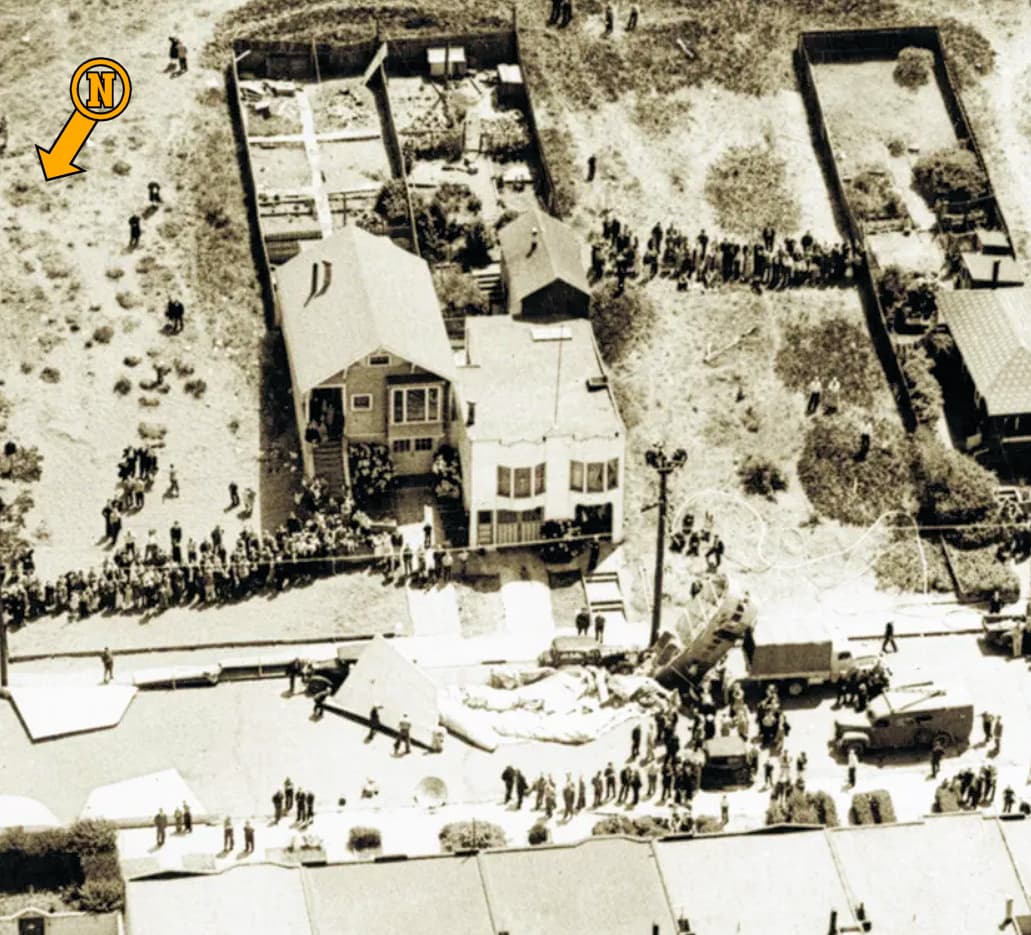

By 11:20 a.m. curious residents of Daly City watched as the partly deflated L-8 drifted lazily toward the Crocker Hills. Some witnesses reported seeing the two pilots inside the gondola while others stated the opposite. Regardless, fifteen minutes after crossing the shoreline, L-8’s journey ended abruptly three miles (five kilometers) inland on the 400 block of Bellevue Avenue.

Pee-Wee says: Here we are over the Crocker Neighborhood, flying east past the 400 block of Bellevue Avenue in Daly City. L-8 landed (1) right here, in front of 423 and 424 Bellevue. These (2) conspicuous, red-roofed homes two blocks west are a great landmark for finding the right spot.

Here’s your homework, friends! L-8 wasn’t the only aircraft that arrived unexpectedly in Daly City during World War 2. On 05 December 1943, Bell P-39Q 44-2437 crashed into the (3) vacant home at 73 Alexander Avenue during a formation training flight, killing pilot 2nd Lieutenant Wallace Hopkins. Another ship from the formation crashed into the Crocker Hills above the neighborhood, killing Flight Officer George Criswell. We don’t have room to cover these accidents in detail, but they’re definitely strange ones and worth some extra reading. The Aviation Safety Network and OpenSFHistory will get you started. Sorry, there’s no extra credit for this assignment!

Daly City encompasses land that once belonged to rancher John Daly. When San Francisco was devastated by the 1906 earthquake, many displaced residents encamped on Daly’s land. The businessman and his neighbors donated food and shelter to the victims and, when Daly later subdivided his land, many of them built new homes here. Fearing being overlooked by San Francisco and San Mateo County, they sought incorporation as a city in 1908. That effort failed, but another vote in 1911 passed, 132 for incorporation and 130 against. The new town was named in honor of Daly and boasted a population of 2,900.

Pee-Wee says: Hold up. 2,900 people, and only 262 voted?

Yes, but less than half that number were eligible to vote. Women weren’t even allowed to vote in 1911.

Pee-Wee says: That’s still only about eighteen percent of the voting population. I guess some things never change.

Pee-Wee says: We’ve turned back to the southwest in this photo. You can clearly see (1) the spot on Bellevue Avenue where L-8 landed. Before settling onto the street, she rolled across the top of (2) Horace and Ethel Appleton’s home at 432 Bellevue and short-circuited electrical lines running along the south curb. The Daly City Fire Department arrived quickly and, finding the control cab empty, tore into the partially inflated envelope to look for the crew.

Not much has changed here since the unexpected guest dropped onto Bellevue Avenue, except for the greatly increased number of neighbors! Looking at aerial imagery and Street View, you’ll note that the houses at 419 and 423 Bellevue, and even the telephone pole the L-8 landed against, look much as they did in 1942.

Pee-Wee says: Here’s another photo from the National Archives, showing L-8’s gondola on Bellevue Avenue, looking south. You can see (1) damage to the Number 2 engine cowl from the blimp’s brush with the cliffs near the Olympic Club. (2) Here’s the 4-inch (10 centimeter) hailing loudspeaker, behind the (3) starboard depth charge rack, used for communicating with ships and personnel on the ground. The port-side depth charge has already been removed in this photo. Interestingly, one of the (4) pilot’s headphones can be seen dangling out the (5) cabin door, which is locked open. All cockpit switches were in their normal positions and all equipment was in place and functioning. The only thing missing was the crew.

Ah, the radio and the hailing speaker. Let’s talk theories again.

The “secret microwave or radar incapacitated the crew and made them fall out” theory rests primarily on one technical fact: L-8’s battery should have powered the blimp for 17 hours but was depleted when the Navy salvage crew arrived, about five and a half hours after takeoff. Those pushing this theory assume that the secret piece of equipment drained the battery. Let’s investigate.

The L-Class blimps were equipped with a single engine-driven 15-Volt DC generator that provided electrical power primarily for the ship’s radios, lights, and engine starters. It also charged the backup 12-Volt, 34-Amp lead-acid battery.

Pee-Wee says: The C/O stated that the L-Class’s meager battery was an ongoing source of concern, and that following a generator failure, it might only provide ten short radio transmissions before being exhausted. Repeated engine start attempts would further reduce that number.

Battery life can be estimated by dividing the available Amps by the load. For example, a 10-Amp battery can power a device that draws 5 Amps for 2 hours. Most experts recommend accounting for only 90 percent of the battery’s charge.

Some researchers point out that the ZP-32 squadron C/O stated that the electrical draw on L-8’s battery was 2 Amps, which is how the “secret equipment” theory arrives at the 17-hour battery life (34 Amp battery / 2 Amp draw = 17 hours). But there’s a problem with that number. Reading the testimony carefully reveals that the C/O was referring only to the Bogen hailing system drawing 2 Amps while in standby mode. The blimp’s radio was also on.

Pee-Wee says: We couldn’t find any data about the L-Class blimp radios, but we can draw some conclusions by examining period equipment. We estimate that L-8’s radio drew between 4 and 5 Amps when “on” but not transmitting.

That puts a total draw on the battery of between 6 and 7 Amps. Assuming 30.6 Amps available (90% of 34 Amps), L-8’s battery life with the radio and Bogen hailer running was approximately 4.3 to 5.1 hours. The blimp’s engines may have failed as early as 0800.

Pee-Wee says: It’s totally reasonable then, if we account for the battery’s usable charge and the actual electrical load, for the battery to be depleted when the salvage crew arrived at noon, without any “extra” equipment running.

Let’s consider one other thing that further discredits the “secret equipment” theory: airborne radars in use early in the war required 28-Volt electrical systems. There is no indication that L-8 was equipped with a “step up” transformer of any sort, and I doubt anyone was running a fancy new radar or microwave transmitter off 15 Volts. And that system probably wouldn’t work at all off the battery’s 12 Volts.

So, there you go: no “spooky” electrical equipment.

Pee-Wee says: So what happened to Lieutenant Cody and Ensign Adams? Expanding on the Navy’s conclusion, we can imagine this scenario:

At around 7:38 a.m. Cody and Adams encounter a suspicious oil slick east of the Farallons, and Cody maneuvers L-8 to investigate. After circling and evaluating the situation, Cody elects to drop smoke flares to mark the location. L-Class blimps weren’t equipped with drop chutes for flares: the crew had to “chuck” them overboard by hand. Ensign Adams collects the flares, opens the cabin door, and latches it open.

Navy crews were proud of their equipment, and L-8’s wooden floor is spotless under its polish, and maybe a little slick from sea spray blowing through the open door. Ensign Adams, like all officers, is wearing a low uniform shoe–a “loafer.” Somehow while dropping the last flare overboard, he slips, tumbles out the door, and becomes entangled in the exterior grip bar or starboard depth charge rigging. He frantically calls for help.

Cody closes both throttles and puts L-8 into a slight climb to keep her from striking the water while he’s away from his station, then moves to the open door to assist Adams. He struggles to pull Adams back inside, and then one or both lose their grips, and both men fall into the water below. They’re wearing life vests, but the impact knocks both men unconscious.

L-8 slows to a stop, but suddenly 350 pounds lighter and already neutrally buoyant, she lunges upwards into the clouds. As her altitude increases, her idling engines eventually sputter and stop, whether from carburetor icing or fouled spark plugs from running too rich at idle. As the errant blimp rises above the clouds, the helium in L-8’s envelope begins heating in the rising sun, pulling the airship higher into the sky. She eventually reaches her pressure height and begins venting helium through her automatic relief valves, then slowly descends back into the clouds until nearly striking the water.

With her helium depleted and her ballonets empty, her envelope can no longer maintain its shape, and the heavy gondola causes her to sag. She slowly drifts eastward and, several hours later, runs onto the sea cliffs, knocking the starboard depth charge from its rack.

Once again freed of weight, L-8 rises back into the sky, but achieves static neutrality quickly.

She drifts inland, dragging over houses and power lines until eventually landing outside the Appleton residence.

The average water temperature around the Farallon Islands in August is approximately 58 degrees Fahrenheit (14 Celsius), and neither crewman is wearing water survival gear. If either survived the fall, they lose muscle dexterity in about 15 minutes and consciousness in two hours. Thanks to confused reports from eyewitnesses, a search isn’t ordered until approximately 12:30 p.m., almost four hours after the men entered the water.

The waters in the vicinity of the Farallons are also rife with adult Great White Sharks, especially in August.

Well. That’s certainly…depressing. Two naval aviators lost, two wives widowed, and a valuable patrol blimp almost lost because of loafers and a slick floor.

Pee-Wee says: It’s purely conjecture, but it’s certainly plausible, at least more so than the other theories. My story didn’t involve strange equipment, G-Men, and aliens, although I would have loved to see Cody and Adams step off the alien “mothership” at the end of Close Encounters of the Third Kind alongside the Flight 19 crewmen. Ready for the epilogue?

Hold on. Gotta’ get more cookies.

Epilogue

Epilogue

Pee-Wee says: Lieutenant Ernest DeWitt Cody was never recovered and, one year after his disappearance, was declared “missing at sea, presumed dead.” A headstone bearing his name was placed at Arlington National Cemetery, Section MJ, Grave 35.

Helen Cody married Edgar Delamater in April 1945. She bore two children–a daughter and a son–and worked as a legal secretary. Helen passed away in 1991, aged 73.

Ensign Charles Ellis Adams was never recovered and, one year after his disappearance, he was declared “missing at sea, presumed dead.” A memorial stone bearing his name was placed in East Los Angeles at Calvary Cemetery, Section R.

Helen Adams never remarried and bore no children. She passed away in 1944, aged 34, and rests beside her husband’s memorial.

AM3 James Riley Hill reportedly regretted not going along on the patrol, feeling certain that he could have prevented whatever happened to Cody and Adams. Before the war’s end, he attended LTA pilot training and served at NAS Hitchcock, Weeksville, and Moffett, and later as a LTA pilot instructor. Hill retired in 1963 and is believed to have passed away in 2022.

Goodyear

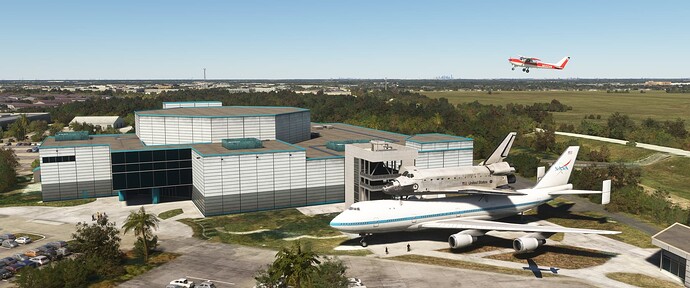

L-8 was returned to Moffett Field and was inspected, repaired, and erected again using a spare envelope. She returned to service in September 1942 and trained Navy LTA crews until the war’s end. Goodyear purchased her control car in January 1946 and stored it with other former Navy blimps at Wingfoot Lake. In 1969 she was rebuilt as the GZ-20 type advertising blimp N10A America and flew from Goodyear’s new base in Spring, Texas. Retired in 1982, her control car was donated to the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, Florida and cosmetically restored. She remains on display today.

Well, that was a long read, wasn’t it?

Pee-Wee says: Yeah, but I finally got it out of my system! We both hope all of you found this tour interesting and informative. If not, then tune in next time for a more conventional tour.

We started writing this one several weeks ago, but time flies, and now it’s the 22nd, so happy birthday!

Pee-Wee says: Thanks, Babe, and thank you for an awesome day: Culver’s for dinner and my very own copy of James Shock’s U.S. Army airships, 1908-1942. Happy happy joy joy!

You’re a woman of simple pleasures.

Pee-Wee says: And by “simple” you mean “inexpensive.”  Anyway, thanks again for joining us on this tour/investigation, everyone.

Anyway, thanks again for joining us on this tour/investigation, everyone.

Do you have additional information or ideas regarding the events of 16 August 1942 or see a flaw in our logic? Feel free to respond here: we’re always open to learning new things.

Pee-Wee says: Bye for now!

![]() I despise progress when it destroys a link to the past.

I despise progress when it destroys a link to the past.